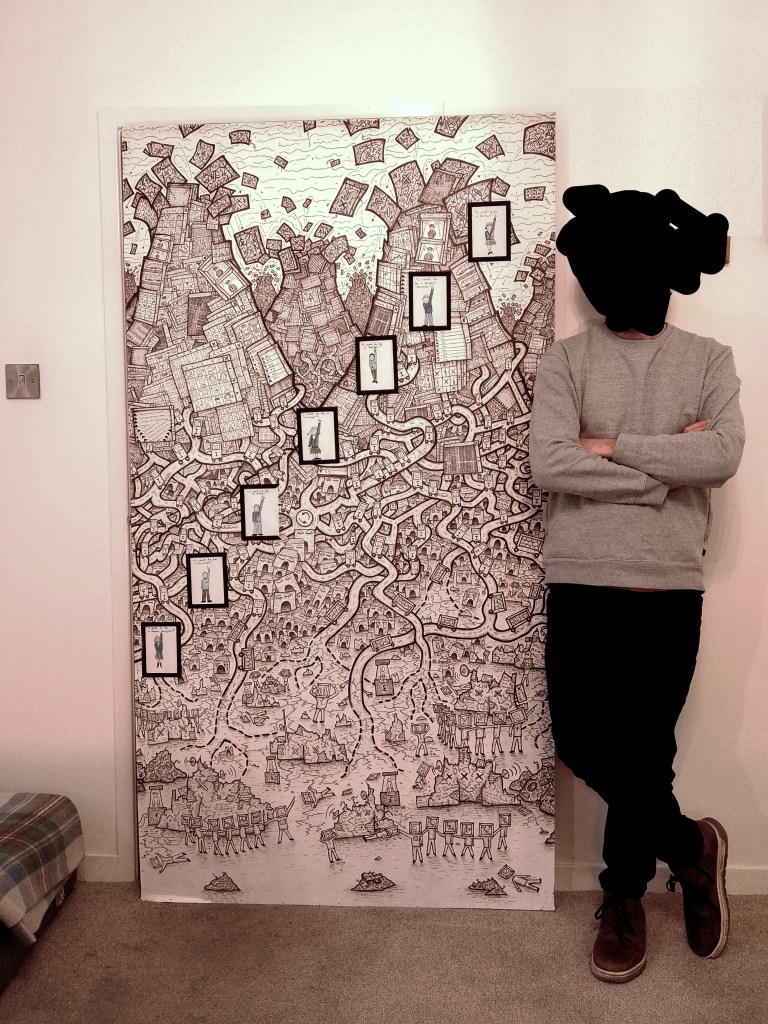

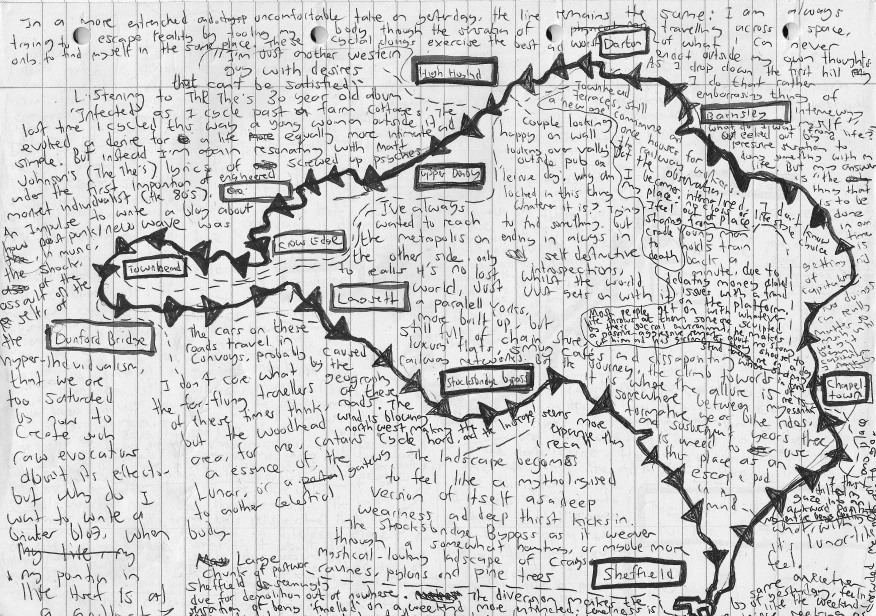

As I begin my ascent up to the tops, I try to break free of my cyclical doings on the foothills, too close to the claustrophobic wrapping of the weekend – an intense atmosphere where I exercise the very best and worst in me. New depths of contempt and idealist manifestos crisscross in my thoughts, like currents formed by arms trying to swim to some sensical space.

“I always end up where I was, and who I was, before.”

The Woodhead pass looks like a river made of Mercury as I recognise it from the midpoint of my ascent, as the sun shines back from countless car roofs making it match with what still seems like a kind of pilgrimage.

And I’ve always wanted to reach the Metropolis on its other side, only to realise it’s no lost world, no place where things are done differently, after all.

I’m still climbing up to my horizon here to see if there is something beyond this reality. And I don’t care what more far-flung wanderers think of this, because this area, for me, sometimes contains an otherworldly essence, like a gateway to another celestial body.

Domestication kicks in and I turn back, perhaps still feeling the weekend pressure.

But Stocksbridge Bypass valley almost breaks me as the thirst and exhaustion kick in. I feel embarrassed by how weak I feel, as the eyes of drivers inevitably scrutinise all objects on this road. The road is weird to begin with, as if it transfers you into a different reality, once you break its brow from the other direction. My weariness and paranoia allow the road to take on an almost mythologised representation of itself, as the ravines, pylons and conifer plantations begin to make the land look consciously inhospitable

By the time I reach Sheffield I’m massively relieved. But not before long I feel estranged amidst the weekend endeavours.

Relief turns into shame, as clothes that seemed fine in my rucksack now form creases that look like the kind sad face that attracts unwanted attention. With these concerns occupying my thoughts every time I see a crowd of revellers, I look for the quieter roads.

Yet, diversion after diversion, as the city demolishes its post-war past, force me back onto the same roads as the revellers. At this point I decide that it’s safe to call it a night, and to start again tomorrow.

Sunday…

There’s strangely a peace to Sunday evenings, that reassures, quells anxieties revved up to max by mid Saturday afternoon.

…it means that our post-working-hour walk up onto the very tops of hills between Yorks and Manchester is going to work out OK today.

It’s September, so the day is still light enough, and the frantic white noise of August has receded.

These barren stretches up here seem to open up the melancholia that hides behind the 24/7 smile of life down below.

Perhaps its truth allows us to feel at ease, ridding ourselves of social status anxiety like removing the weight of a poorly-designed work uniform.

Even if one walked too far into this early autumn sunset, there would be no anxiety, not even in mortal danger– all you would have is clean fresh fear, a sensation that is somewhat different from the humiliating stink of anxiety that clings to us down below.

We look over to both Saddleworth Moor and Holme Moss.

A beginning. Or the ending?

Reaching land’s end, within the land.

This area is like a frontier, even if there turns out to be nothing beyond it.

Nothing more down there…

We look down to where the first few cluster-settlements start to draw out the beginnings of a Greater Manchester sprawl that changes from cobbled-stone to glass and concrete within our hazy horizon.

We then look at the point where the green farming land gives up to the desert-like tops. End and beginnings that illustrate how it all began, and then spread everywhere else.

Like the streams that flow down to form the necessary rivers of this ‘first’ industrial city, I think of the flows of people coming down from these hills, the upheavals, the Peterloo Massacre, the endless rows of workers crammed together, the hopes, aspirations for something better, which informed a pop music that in turn informed the world.

All for what? A single slot of competition in consumption? An Instagram App on an Iphone? An overpriced hovel overlooking other, lesser, hovels?

Surely this can’t be how it all ends?

The silence up here separates it from everywhere else below on this noisy land. As up here, like staring at the sea, or into space, you can see things move before you can hear them moving. In a noise-filled age this is almost non-existent.

What is the use of thought down there, when it seems reduced to shards of information in perpetual battle for dominance with one another? These monochrome colours and featureless plains help bleach that noise, opening our eyes like portals to a frontier out of which sprung our industrialisation, and into which we see a space waiting, waiting, and waiting, to be filled by a future.