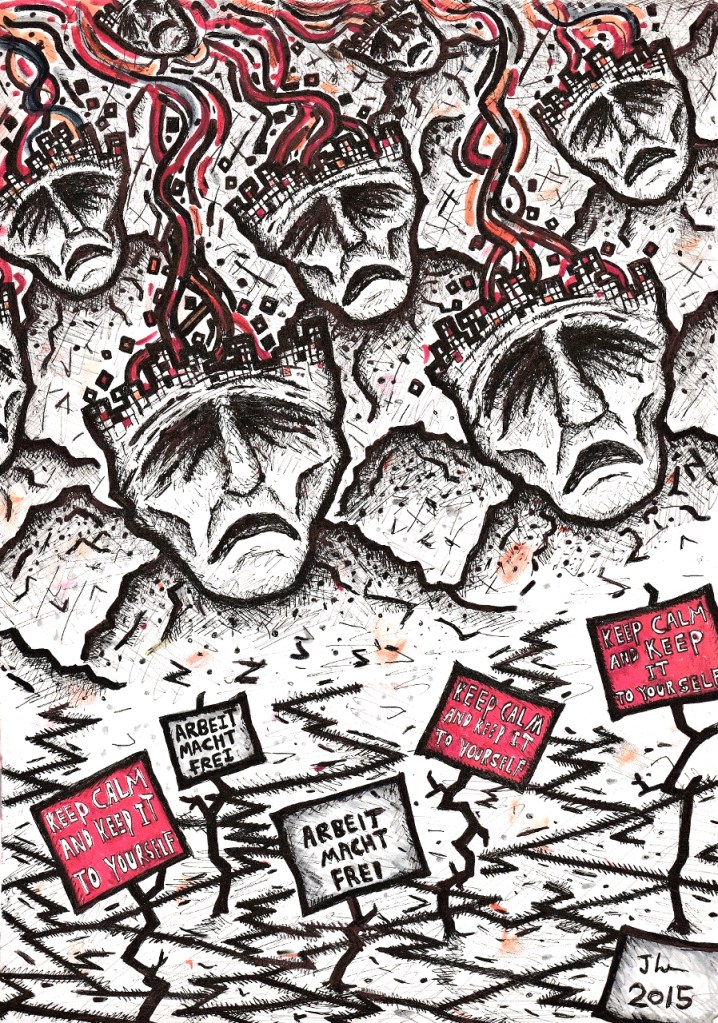

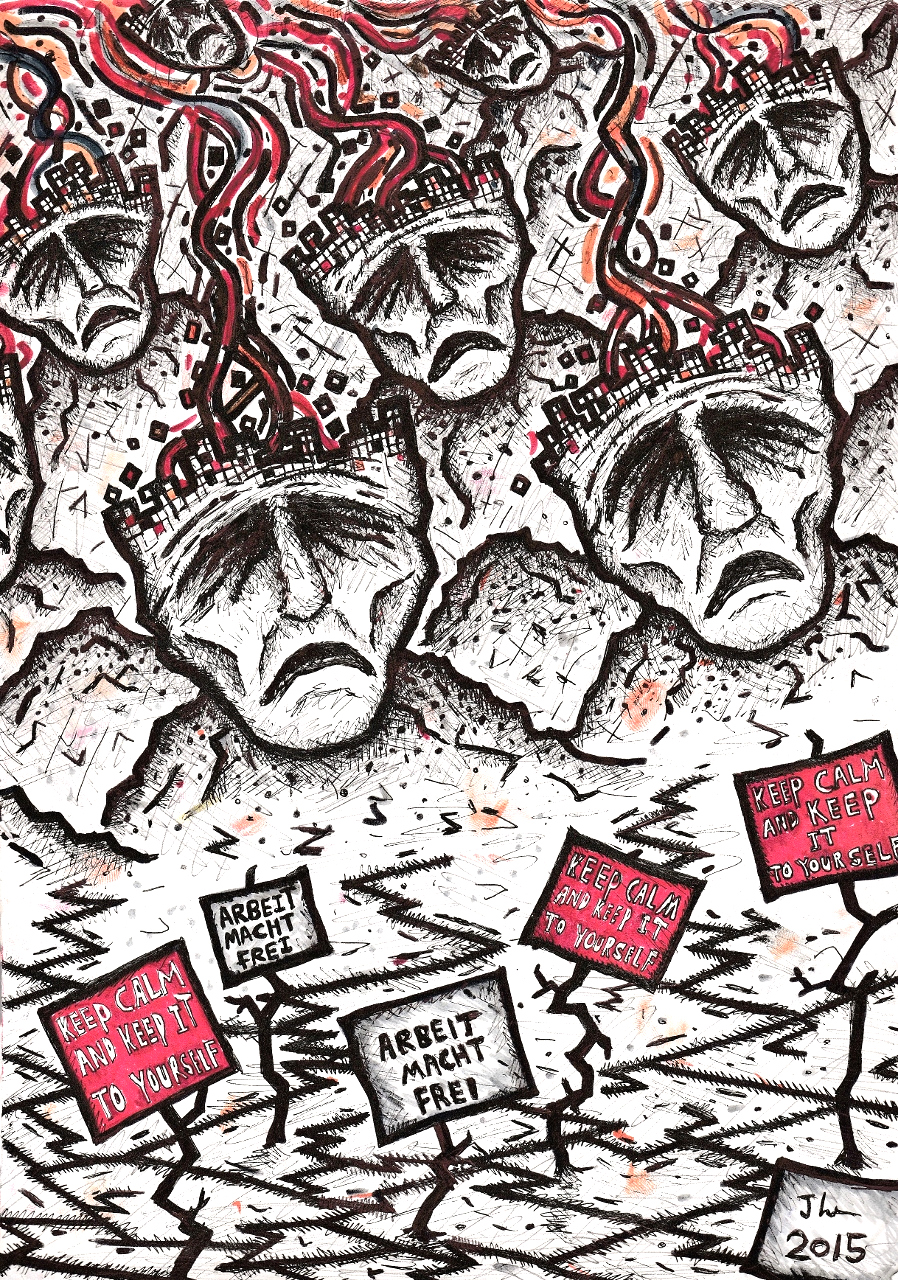

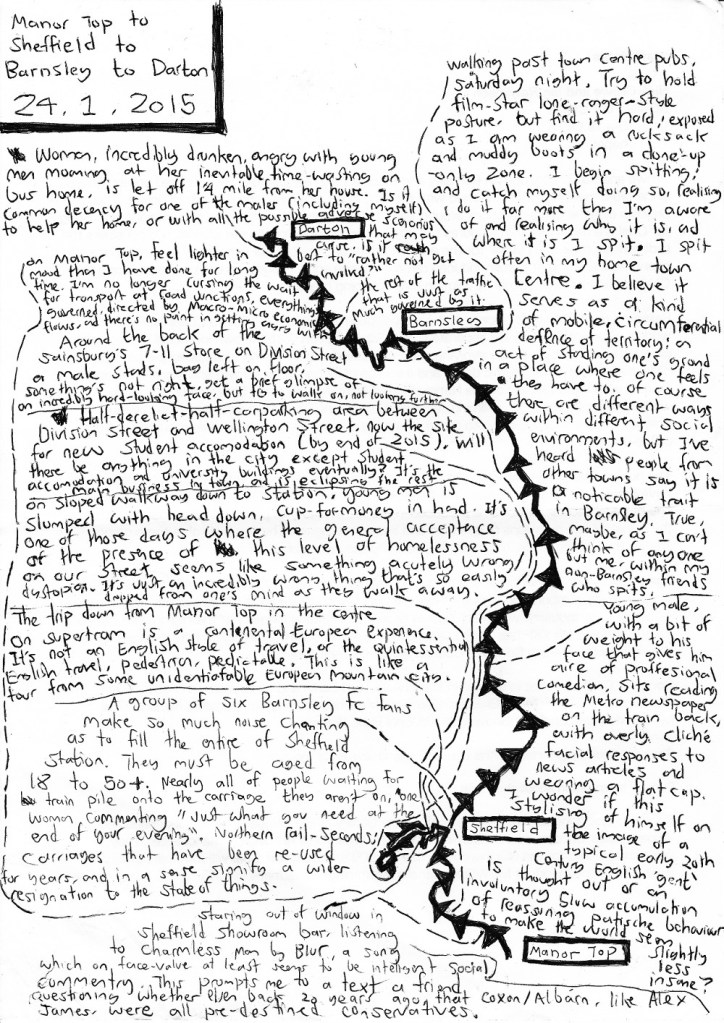

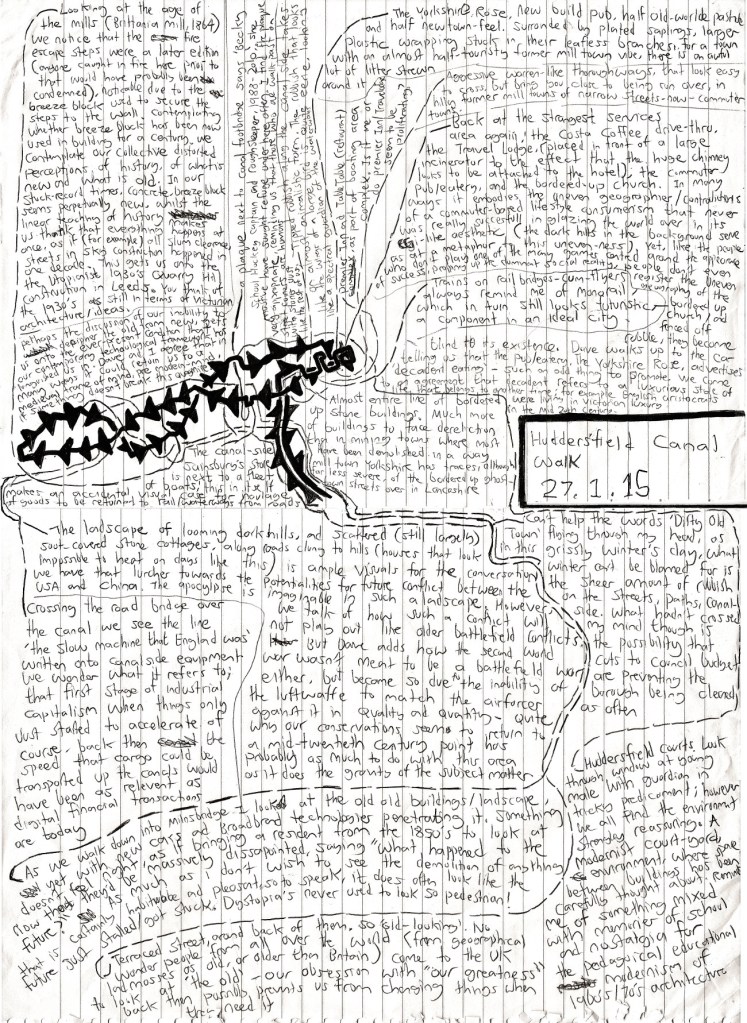

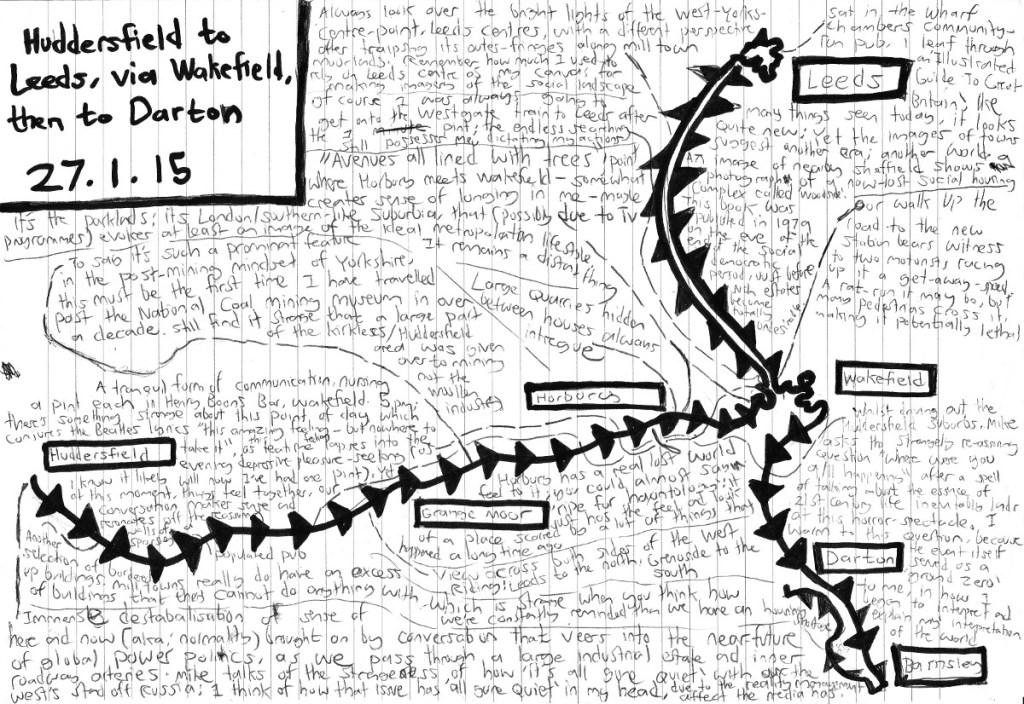

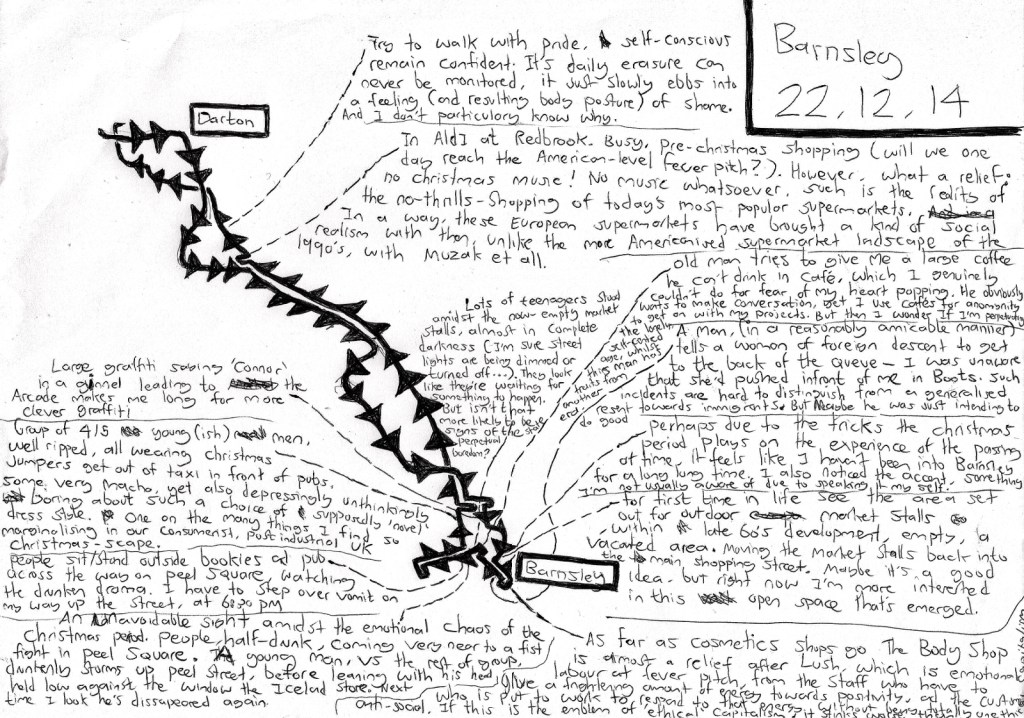

A Cognitive Austerity, ink on paper, A4

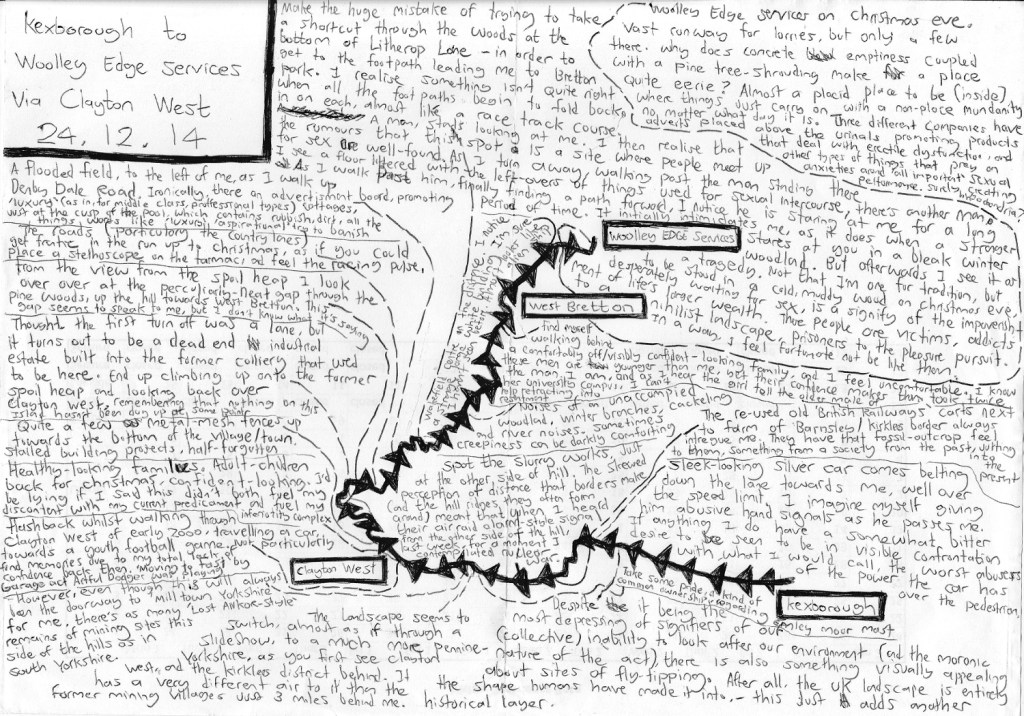

A Cognitive Austerity, ink on paper, A4

I wrote this over a year back, but I have re-posted it as I feel it’s the most sufficient thing I have on me to try to persuade people away from allowing their misery-filled hearts to guide them into re-electing the Tories. I beg you to watch this entire film tonight before you go to the voting booth tomorrow.

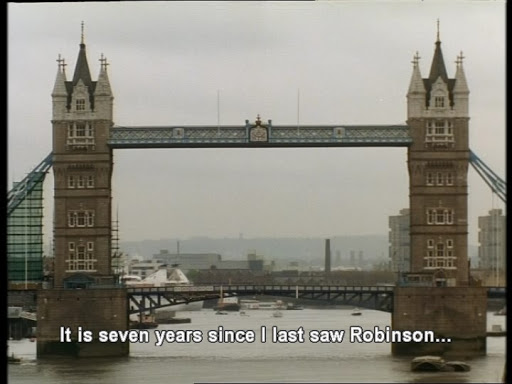

Due to recent thoughts I felt the need to both reference and praise the artist/documentary-maker Patrick Keiller’s 1994 film London; a filmed about a journey through London, which forms a beautiful protest and desire for Justice in a time of loss of belief in a future

Although it should be a suggested alternative watch to Mind The Gap: London vs The Rest, the ‘documentary I criticised on here a week back, I am referring to it here largely due to recent concerns I have been sharing with friends that the Tories may somehow be reelected. This current government [the coalition by name, an unelected Tory coup by nature) thrive off apathy, our sense that there’s nothing we can do.The more apathetic we become, the more powerful they. They are parasites of pessimism.

I reject the idea that I am a pessimist: I am incensed with the injustice in the world/forced to look at what is happening to the world because I cannot stop caring. Pessimism is when you don’t care any more. I may focus on the what’s going wrong, rather than how things could be better, but this isn’t because I don’t care or desire for things to be better. My heart often feels like it is slowly turning to stone, but yet there still remains a Utopianism within me.

Of those I’ve been speaking to we know our society well enough to understand why it may support something that can only maintain/enhance the silent miseries and frustrations; a resignation to all outside our family units and a bizarre fearful distrust in anything that could promise to make life better for us. Yet it remains baffling and relatively impossible to articulate why this happens. Yet this film uses a journey through London to almost map out a diagnosis of the illness stunting society. The real-felt consequences of the re-election of the Conservatives is well illustrated by the worried anticipations of the narrator and Robinson (whose life the art-documentary is based around) on the days surrounding the 1992 Tory reelection. Furthermore, I feel this description that I have used below must be familiar to most of us in contemporary Britain, if we are honest with ourselves, regardless of how 2014 compares to 1992.

[pre-election] “I expected the [Tory] government would be narrowly defeated, but Robinson did not trust the opinion polls, which were in any case showing a last minute drift away from Labour…[post election]. It seemed there was no longer anything a Conservative government could do to vote it out of office. …[T]he middle class in England had continued to vote Conservative because in their miserable hearts they still believed it was in there interest to do so.”

[The expected consequences] “His [Robinson’s] flat would continue to deteriorate, and his rent increase; he would be intimidated by vandalism and petty crime; the bus service would get worse; there would be more traffic and noise pollution, and an increased risk in getting knocked down crossing the road; there would be more drunks, pissing in the street when he looked out of the window, and more children taking drugs on the stairs as he came home at night; his job we be at risk, and subjected to interference; his income would decrease; he would drink more, and less well; he would be ill more often; HE WOULD DIE SOONER” (London, Patrick Keiller, 1994)

I’m no defender of New Labour (I hate the small-minded arguments that try to pit the two parties together as being the full scope of possibilities of how our society could function), but I have definitely noticed many changes since 2010 (since the Tories got back into power), in the news, in the street, in my friends’ lives, in my life, that chime with the description above. The increase in cars on the road – as if somehow the increased psychological pressure of a more harsh, unforgiving, yet deliberately imposed reality onto people, has pushed us into using the form of transport most naturally at home with self-centredness – a pessimism reinforcing itself; as we no longer even dare contemplate the environmental consequences of this anymore. I am always expecting violence, self-inflicted and aimed at others; the nearby city of Sheffield seems to have had an increase of both homeless individuals; in my home town Barnsley, individuals evidentially being crushed by this imposed reality, due to the often-seen inability for rage to be controlled, whether it is aimed at others, or at themselves. I sometimes wonder whether we are a society of taught masochists wanting pain from the public school boy sadist-rulers. But there again, anybody who hasn’t become the ideal-functioning man-capital, must be wondering how much more they can hide from, and whether they will be in-front of the crusher sometime soon. How much can a “miserable heart” take, before it retaliates?

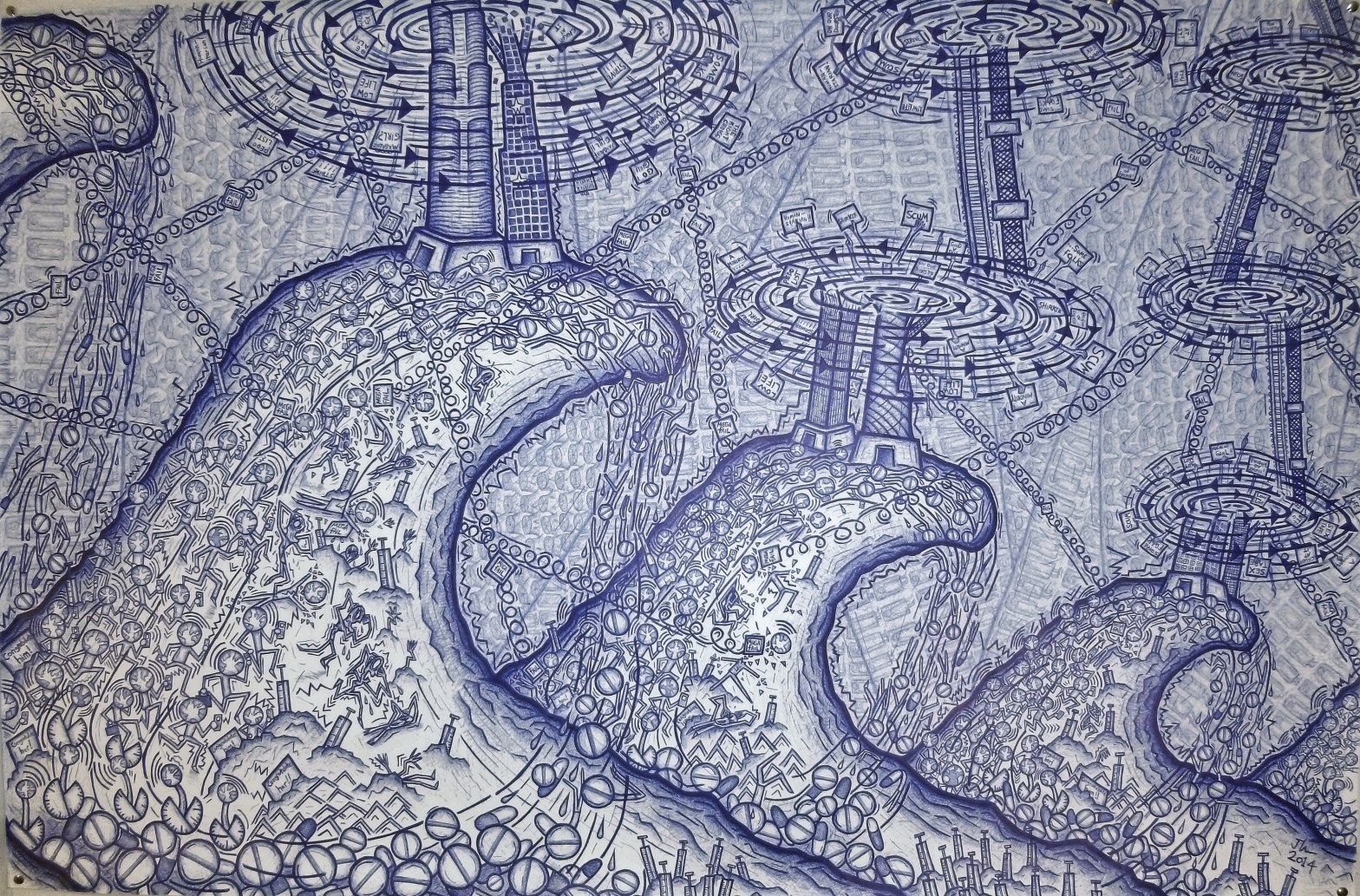

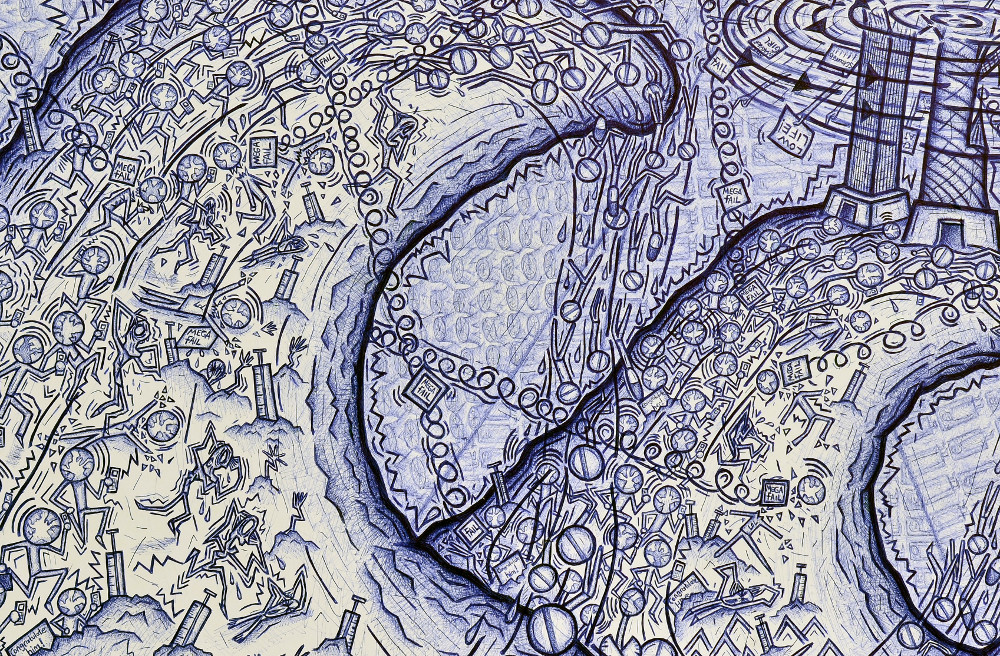

Not Humanly Possible, A4, ink on paper

‘The past is another world’. Indeed it is, full of lost what-might-have-beens. I cannot even begin to estimate how many calories and hours were put into making these works that were heading in a more-painterly/sculptural direction, nor the lost might-have-beens that may have constituted an alternative usage of that time. Dating from the bright-eyed-dawn of the perceived-shirking-of-tangled-up-teenage-trials of my very early 20’s in 2004, to works made in the infancy of the long night that proceeded from the 2008 crash, these works now seem to me like surfaces of an (un)realised planet.

Due to this they just don’t fit anymore, like architecture that has lost its aesthetic function within the light of a new kind of world, the demolishing of them was the last necessary act. Reality has changed, and they are worth more to me now as documentation of an excavation of that past reality that I cannot go back to (all a poetics perhaps [?] devised to acclimatize myself to the truth: that I had no longer have storage space for works that were becoming increasingly smashed to pieces in narrower and narrower confines).

However, perhaps what surprised me the most, and possibly came close to preventing me smashing up any more of the works, was that the paint was still wet on the inside of one of the pieces from 2007. The smell of gloss and oils momentarily taking me back to 2007…even the music I listen to from such times seems lost as if submerged under a mudslide.

Stories From Forgotten Space builds on 2014 Mapmaking with the aim of taking the most prominent features of the project a little further.

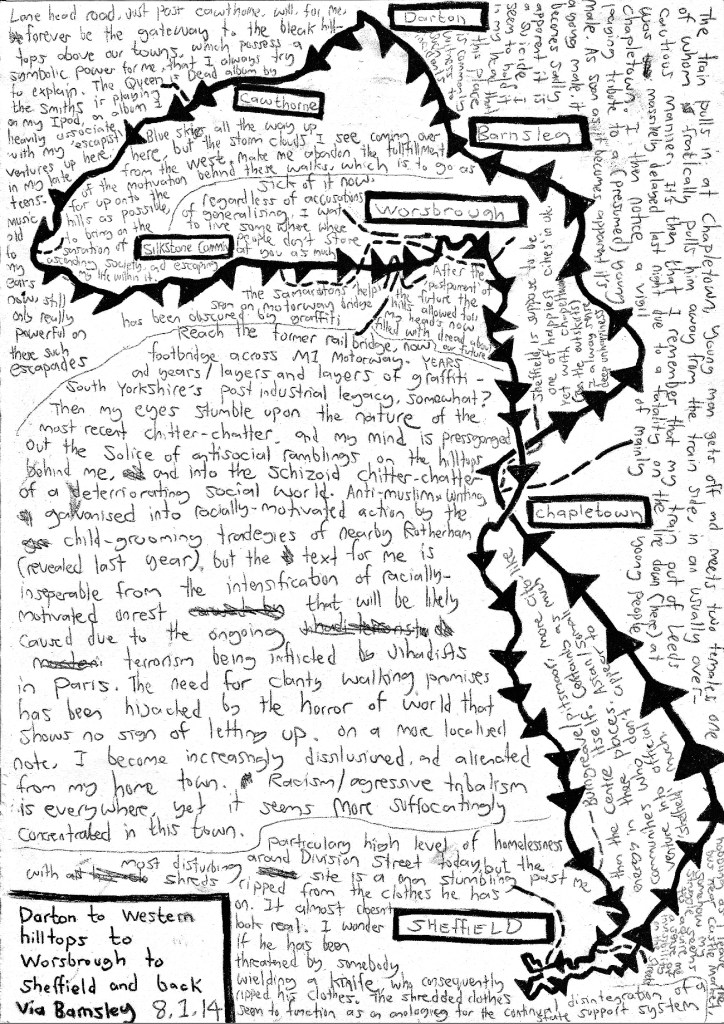

8 January

“Lane Head Road, just past the village of Cawthorne, will, for me, forever-be the gateway to the bleak hilltops above our towns, which possesses a symbolic power over me, which I ceaselessly try to explain. The Smith’s The Queen is Dead album is playing on my IPod, an album I heavily associate with my ‘escapist’ ventures up here in my late teenage years – specifically in the wake of the 9/11 terror spectacle. Music that is old to my ears, now only retains the power it once had over me whilst on these such escapades.”

“Blue skies all the way up, but the storm clouds I see coming in over from the west make me abandon the fulfilment of the motivation behind these walks; to go as far as I can up onto the hills as possible, in order to bring on the sensation of ‘climbing out of society’ and escaping my life within it. ”

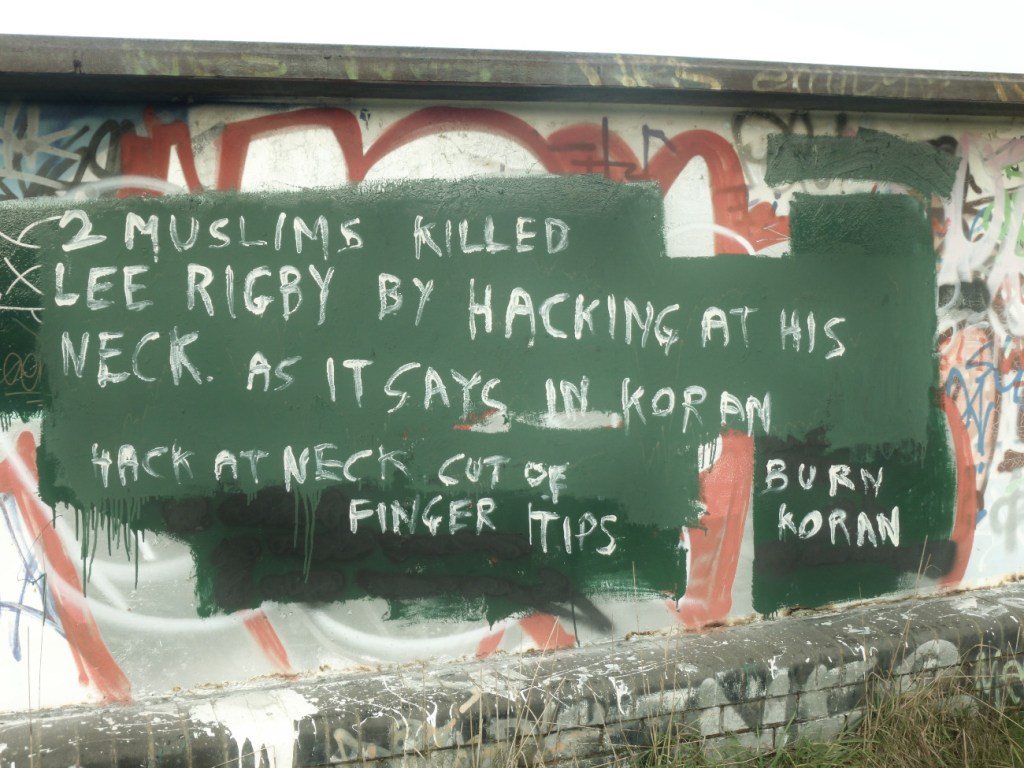

“After the postponement of the future the hills allowed for, my head’s now filled with dread about our future. I reach the former railway bridge over the M1 motorway. Years and years of/layer upon layer of graffiti covers the bridge’s interior sides. South Yorkshire’s post-industrial legacy somewhat? Then my eyes stumble upon the nature of the graffiti. The chitter-chatterings of the now displayed in these words press-gangs my mind out the solace of my antisocial ramblings upon the tops and into the schizoid endless chatter of the deteriorating social world. Anti-Muslim sentiment galvanised into racially-motivated painting action by the child-grooming disgraces in nearby Rotherham (revealed last year). For me, the text is inseparable from the likely intensification of racially/ethnically-motivated unrest due to the ongoing terrorist attacks and terrorist pursuits in Paris. The need for the clarity that walking promises to give me, has been hijacked by the horror of the world that shows no sign of letting up. On a more localised note, whilst racism and aggressive tribalist assertions are everywhere, they seem more suffocatingly concentrated in my home area, give me intermittent bouts of severe estrangement/alienation from it.”

“Particularly high amount of homelessness around Division Street today, but most striking, and equally disturbing sight, is of a man who comes stumbling past me in shredded clothing, in a manner that doesn’t even look possible without accompanying slices into his flesh. It almost doesn’t look real. I wonder if he has been subjected to an array of threatening gestures from a knife-wielding individual he has been unfortunate enough to stumble into due to his (likely) circumstances. The shredded clothes seem to function as a metaphor for the continual disintegration of the state-support system.”

“The train pulls in at Chapletown. A young adult male gets off and meets two females, one of whom manically drags him away from the platform, and to an over-cautious distance from the train. It’s then that I remember how we were massively delayed in catching the last train out of Leeds last night, due to “a fatality on the line” down here at Chapletown. I then notice there is a vigil ongoing, mainly consisting of young people paying tribute to a young male. As soon as it becomes apparent it was a young male who died, it sadly becomes apparent that it was a suicide. I seem to hold it in my head that there has been a spate of suicide incidents around this area of the railway line over the years. Sheffield is apparently one of the ‘happiest cities in the UK’, but with the Chapletown area on the outskirts, I might be wrong, but I get a feeling that deep unhappiness resides here.”

.

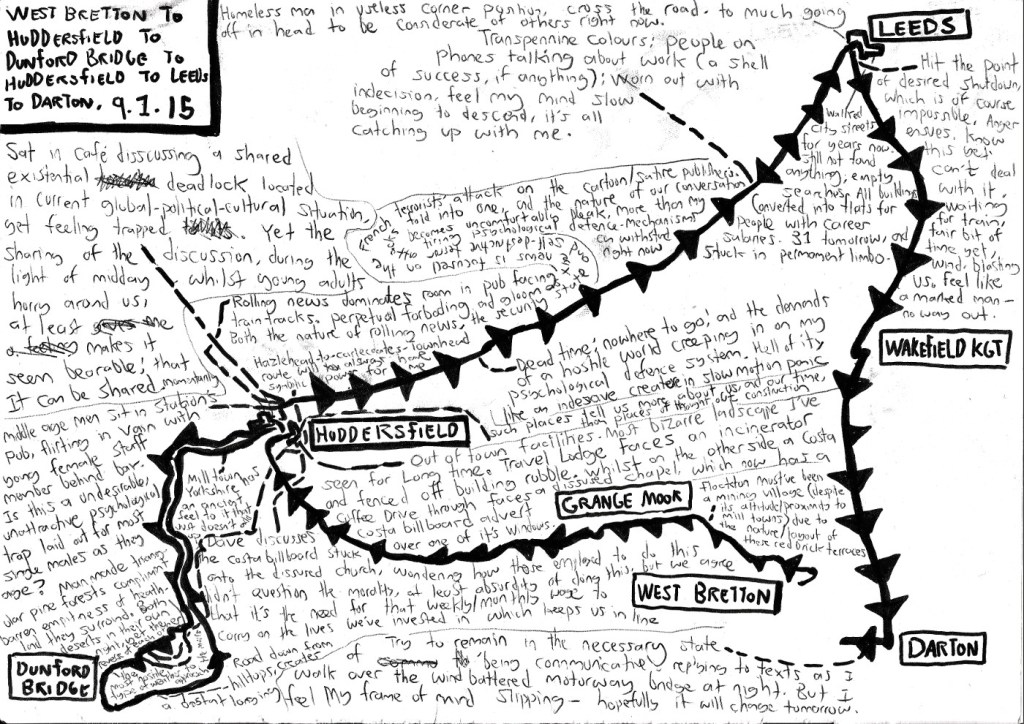

January 9…

“Sat with Dave in popular cafe in Huddersfield centre, discussing a shared sense of existential deadlock, located amidst the the fog of the global-political-environment-cultural deadlock. Yet, the very sharing of this discussion, amidst midday urban life, whilst young adults (seemingly still possessing vitality) hurry around us, at least makes it all seem bearable, possibly making it even all seem solvable.”

“Mill-town Yorkshire has an ancient feel to it that just doesn’t add up.”

he road down from the hilltops gives me a distant longing for something.”

“Rolling news dominates the room facing the train tracks in Huddersfield train station pub. Perpetual foreboding and mute-panic. The news is focussing on the terror attacks on the offices of cartoonist/satirist Charlie Hebdo. The nature of rolling news, it’s enlargement of the symbiotic-extrapolation of both the security-obsessed state and self-destructive terrorism , acts as a potion unleashing panic and abjection in the mind (tightened facial expression/heavy brow – physical reaction). The nature of our conversation becomes uncomfortable. More than my tired psychological defence-mechanisms can withstand right now.”

“On the train to Leeds. Dead-time ‘nowhere to go’, and the hostile demands of the world creeping all over my psychological defence-mechanisms. The hell of it; like a indecisive creature in slow-motion-panic under slowly advancing headlights. Transpennine Express colours; people on mobiles talking about work (a mere shell of success maybe, but right now it’s convincing). Worn out with indecision. Feel my mind slowly beginning to descend – all catching up with me.”

“In Leeds. Walked these city streets for years now – still not found anything; empty searches. All the buildings I stare at being converted into flats for people with career salaries. 31 years old tomorrow, and stuck in permanent limbo.”

.

January 24…

“Staring out of window of the Showroom bar, listening to 1995 chart song Charmless Man, by Blur. A song, which on face-value at least has the air of intelligent social commentary. This prompts me to text a friend questioning whether, even back all those 20 years prior the current establishment placing of the band’s members, that Coxon/Albarn, like rich-man-host Alex James, were all predestined conservatives, if not by name, at least by nature.”

“On sloped walkway down to Sheffield train station, a young man is slumped with his head down close to the money-cup he holds out. I think I’m having one of those days where something seems acutely wrong/dystopian in (what appears to be) a general acceptance of the presence of this level of homelessness on our streets. It’s just an incredibly unwarranted aspect of reality that drops from ones mind as soon as they walk away.”

“Young man, with a face quite similar to iconised-as-northerner Peter Kay, sits reading the Metro paper on the train back to Barnsley. Wearing a flatcap, he makes overly cliche facial responses to what he is looking at in the newspaper. I wonder if this stylising of himself on the image of an early 20th century English ‘gent’ is something he has thought about, or whether it is an involuntary slow accumulation of reassuring pastiche-behaviour to make the world seem slightly less insane.”

“Walking past [Barnsley] town centre pubs, at about half ten on a Saturday night, I try to hold a film-star lone-ranger-style posture, but find it hard – exposed as I am, wearing a rucksack and muddy boots in a done-up-only zone. I begin spitting – and I catch myself doing so, realising I do far more than I associate myself with the act. I begin to realise why I do it. I spit often in my home town. I think it may serve as a kind of mobile, circumferential defence of territory; an act of standing one’s ground in a place where one (at least) feels they have to. Of course, there are different ways of doing this within different social environments, but I’ve heard people from other towns say it is a noticeable trait in Barnsley.”

January 27…

“Despite Seeing the Void where the markets were a few times already, it still catches me by surprise. Since I’ve known the town centre (from very early on in my life) the market has been in that location. Yes, things move on, but there’s such a huge gap/hole here now that it cannot but be glared at by passers-by.”

“End up gazing at the well-thought-out display of chocolate bars and gossip magazines that greets you at counters in the Wilkinson’s Store. I initially contemplate the aged-quality of such a display, still promising the New of sugary stimulation and titillation. It looks so ‘lost world’ somehow. Yet it’s still here. I contemplate whether the reign of physical-item-sugary-consumables would fall if it was without its counterpart of immaterial-sugary-consumables that energise our aspirations to be part of the system…”

“My ‘Mary Celeste’ building, the structure I saw as symbolic of the ‘stuck record’ period we lapsed into fully after the 2008 financial crash (the building was left in a skeletal form since that point) is finally being completed. Supposedly this would mean that if the ‘going through the motions like ghosts’ was the result of the crash then it is over now. But I don’t think so. Like much of the talk about ‘economic growth’ at the moment; the cladding on this construction merely covers up the lack of any genuine advancement; it’s just a mindless drive with no purpose or justification; the dominant agenda still remains defunct.”

” The 50+ year old Beach Boys track I Get Around comes on the radio in the cafe in the Morrisons next to Barnsley centre. But everywhere is currently the cafe lost in time at the ending of the TV series Sapphire and Steel. An entire culture dead, but on endless repeat. Disturbing when you contemplate it.”

“The broken-in-half effect that the low-lying clouds make of the Emley Moor Signal mast prompts Michael to talk of a production he remembered watching in Sheffield, about how civilisation will collapse if we carry on consuming and relying on oil in the way we do. He brings this up because he recalled on how driving home he looked towards Emley Moor, imagining its lights gone out; a cold, grey monolith, surrounded by a dark-aged, barren world below.”

“Passing trains on railway bridges-cum-flyeovers remind me of a monorail system which, in turn, still seems futuristic; a component of an ideal city”

“Arrive back at the strangest services-area again; the Costa Coffee Drive-thru, the Travel Lodge (placed in front of the incinerator to the effect that the massive chimney looks to be part of the hotel), the commuter-pub/eatery, fenced-off building rubble, and a bordered up church. In many ways it embodies the uneven geographies/contradictions of a commuter-based Life-style Consumerism that has never really succeeded in glazing the the world over in it’s ‘CGI-style’ landscaping (the dark hills that loom over us in the background seem an ample metaphor for this unevenness). Yet, as people who don’t play one of the many games centred around conjuring the appearance of success/glamour (which in turn props up the entire social system) aren’t even registered and lapse into social blind-spots, the same can be said of the bordered up church, and fenced-off rubble, as the people coming out of Costa are utterly oblivious to them. Dave walks up to the car to meet me and Mike, telling us that the pub/eatery, ‘The Yorkshire Rose’, advertised ‘decadent eating’ – surely an odd thing to promote? We come to an agreement that decadent refers to a luxurious way of living that belongs to another time; an example of this would be the English upper class living in Victorian period luxury well into the 20th century.”

“Tipped rubbish next to canal-side takes on an almost animalistic form. The rubbish that looks like the wings of a large bird is quite eerie – looking like a spectral guardian of the waterways”.

“A plaque next to the canal footbridge says ‘Becky, 1988-2010, Captain of the school hockey team and rough sleeper, stayed here 2008-2010’. I find the plaque very agreeable, reminding us that those whom we walk past on street corners, rarely even acknowledging their existence, are humans with stories like the rest of us.”

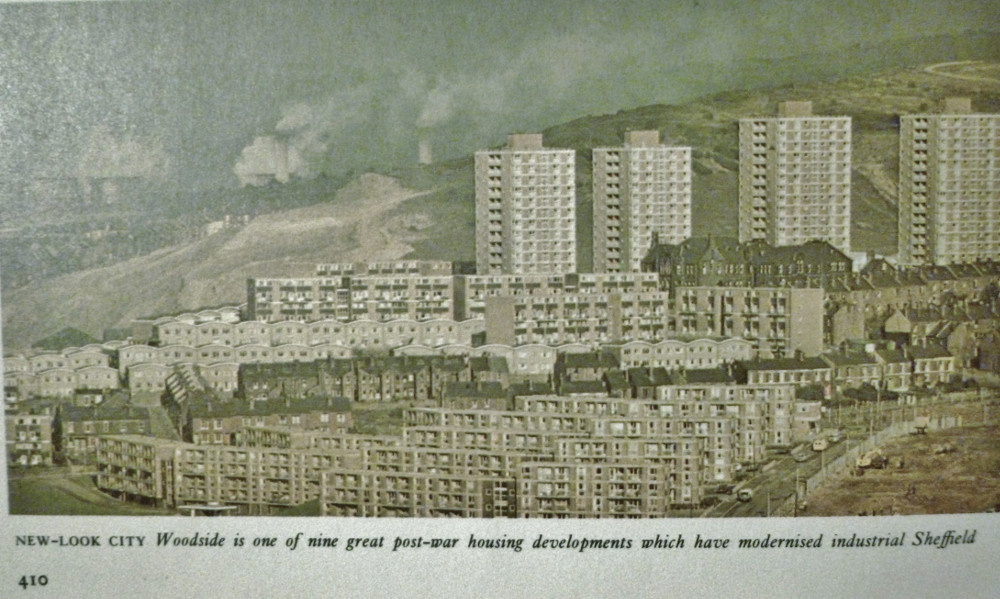

“Looking up the old mill building (Brittannia Mills, 1864), we notice that the fire escape steps were a later edition (anyone caught in a fire here prior to their construction would’ve likely been instantly condemned), noticable due to the strange addition of breeze block, to Yorkshire Stone, used to secure the steps to the building. Contemplating whether breeze block has now been used in construction for a century, we contemplate our collective distorted perceptions of history, of what’s new and what’s old. In these ‘stuck-record’ times, concrete and breeze block seems perpetually near-past, whilst the linear teaching of History makes us believe that everything that is similar must’ve happened at the exact same point. As if all slum-clearance happened in one decade. This leads us to talk about the utopianist 1930’s Quarry Hill construction in Leeds. Now demolished, but once a forward-looking project, you tend to think of the 1930’s still in terms of Victorian architecture/ideas.”

As We Walk into Milnsbridge I look at the old old buildings/landscape. Yet with new cars and broadband technologies penetrating it, Something doesn’t feel right. It feels that if one had the ability to bring a 1860’s resident of this area into its present-day reality, that they’d be massively disappointed in a way, asking “what happened to the future?” As much as I don’t wish to see the demolition of anything that certainly still habitable and pleasant, so to speak, when you glare at the present world it does often feel like for many things the future got stuck, whilst other bits of the future carried on. All in all Dystopias never used to look so pedestrian!”

“Immense destabilisation of here and now (a.k.a normality) brought on by conversation that veers into the near-future of global power-politics, as we pass through a large industrial estate and over inner ring-road arteries. Michael talks of the strangeness of how “it’s all gone quiet” with the West’s stand off with Russia, coupled with the strange recent drop in oil prices; personally, I think of how this issue has “all gone quiet” in my head, unquestionably down to the reality-management affect the omnipresent media outlets have.”

“Horbury has a real ‘lost world’ feel to it. You could say it was ripe for hauntology, having the feel and look of a place (to a passer by) of a place laden with the shells of past happenings.”

“A tranquil point of communicating, each nursing a pint, in the Henry Boons pub in Wakefield, 5PM. I’ve always found there to be something strange about this time of day, roughly articulated by the Beatles lyrics “but oh, that magic feeling [but] nowhere to go”, as this tea-time feeling lapses into the evening’s depressive-pleasure-seeking (as I know it likely will now I’ve had one pint). Yet at this moment, things feel together, connected, our conversation makes sense, and resonates off the walls of this half-empty pub.”

“Sat in Wharf Chambers, a not-for-profit-cooperative pub. I leaf through an AA Illustrative Guide To Great Britain. Like many things seen on today’s travelling, it looks quite new. Yet the photographs of towns suggest another era, another world. A photograph of nearby Sheffield a now-lost social housing project called ‘Woodside’. It turns out this book was published in 1979, right on the eve of the end of the social democratic project period, just before such estates became continuously less and less desirable.”

Reflections gathered from performance in the Anti-Gallery Show, weekend 16,17,18, January 2015

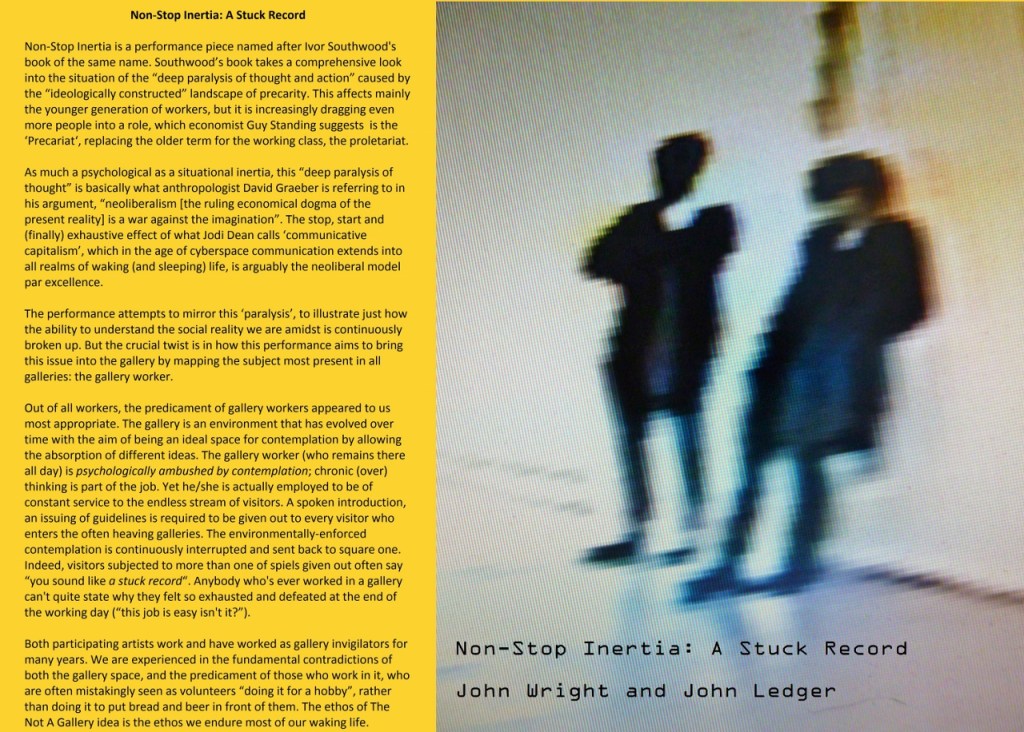

This text is a reflection on the performing of Non-Stop Inertia: A Stuck Record – inspired by Ivor Southwood’s book Non-Stop Inertia. Part of a wider collaborative project between myself and Leeds-based artist/curator John Wright, Non-Stop Inertia was played intermittently over a 3 day period as part of the Anti-Gallery Show, at The Espacio Gallery in Shoreditch, London. As this text deals purely with reflections during and after these 3 days, the explanation for the motives behind this ongoing work can be found here: https://johnledger.wordpress.com/2014/12/07/non-stop-inertia-a-stuck-record-the-anti-gallery-show/ . However, the writing uses other points within the 3 day period in London to talk about a larger project, in which Non-Stop Inertia is just one part.

A Psychological Experiment…

That I am in a well-and-truly-spent state the day after our Non-Stop-Inertia piece means that if it was as much a psychological experiment as it was a piece of artwork then the experiment was successful. The carefully-chosen texts we chose to read out were so fitting, but fitting within the eternal-now, ‘in the loop’ of the performance. Because the gravity of their content could as easily fall from mind as it could be put back there once there performance resumed. The content itself became looped; there was no further level of understanding. It was the poetry of a ghost trapped in the machine.

No Evolution

And ghosts trapped in the machine we became. Neuro-psychically electrocuted by the randomly occurring door-alarm signal, I for one can testify to the physical effect (in my manic body movements) that such internalising of the constant expectation of random interruptions can have. Certain lines read out from our texts would land in unison on the pulse-line of the subjectivation, at which point we’d look to each other as if to confer “yes, that’s what this is, exactly!”, but cognitively building on what was being said/read felt impossible due to this anticipation of interruptions. How can you build on things if you are in a perpetual state of siege?

The door alarm noise signaling our ‘calling’ to disseminate emotionally-laboured welcoming-spiel (language absent of life aimed at an absent customer) was, of course, implemented in a random-fashion by our own design. But the intention was to show how this unending anticipation of unpredictable interruptions of our thoughts is a constitutive part of contemporary life, which (we believe) is intrinsic to the inability of individuals and societies alike formulate, or even imagine, a way out of the current global cultural situation that consumes the hopes, desires and visions of alternatives with the same level of ferocity that it consumes the people and resources needed to constitute a future world full stop.

We came away from this performance with no answers to this, but this was the intention: to give poetic form to the very structures preventing us from finding the answers to the current situation. We believe that if the structures permeating contemporary life are dismissed as irrelevant to the task of building towards an alternative, then any kind of positive alternative is impossible.

No Desire to Converse

Whilst in London, myself and John Wright frequently discussed the difference between desire and drive: that, in an ‘always on’, no-future, hyper-competitive, hyper-capitalist world, desire is both short-circuited and disemboweled from drive. This leaves us trapped in a ‘nothing-left-but…’ state, where we often feel a zombie-like-entrapment to the motions of tasks, duties and habits and especially the end-game pursuit of sugary, narcotic, or sexual stimulus; that can often feel like being in a state of seizure due to inconceivability of there being anything else we can do “but pursue pleasure”. (an overly referenced section of Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism book, which I attempted to read out as part of the performance).

As well as the resulting post-performance-state leaving us in a state of incomprehension of what we could possibly do except going and getting alcoholically intoxicated in the city, the performance itself also functioned through pure signal-actioned drive. The words were spoken out of drive, rather than desire. This is why others who attempted to engage in the dialogue, and who weren’t used to the nature of the represented job-type to an extent that they could ‘go through the motions’ like we could, very quickly became frustrated (as was partly the intention). One of the participating artists in the Anti Gallery Show said he couldn’t see the point in trying to make conversation. What was the point of him trying to gain something from a conversation if he was to be constantly sent back to square one by the interruptions?

If we are correct in viewing this predicament as endemic in contemporary life, could it not be said that the breaking down of thought and communication to a sound bite-form isn’t merely the result of a reduction of our attention-spans caused by our immersion in cyberspace, but is actually caused by the lack of desire to engage in conversation due to the anticipation of interruptions slicing through it? We also argued that the increasingly competitive nature of contemporary life further reduces the room for conversation, because the constant sense of the self-under-siege within such a competitive world makes it seem an immediate necessity to get our point heard rather than allow the time for other points to be heard (I, for one, am very guilty of this). Indeed, what was left of our broken up conversations was used to discuss the breaking up of dialogue intrinsic to one of the largest social media platforms: Twitter.

All in all Non-Stop Inertia: A Stuck Record was successful – too successful perhaps; afterwards, the necessary walk (climb) back to Kings Cross station seemed almost daunting.

The (Un)realised Project

This inability to transcend, to get beyond the “this is so relevant!” point whilst we were reading the texts/debating perhaps makes Non-Stop Inertia:A Stuck Record pivotal to a wider sensation myself and John Wright are investigating. That, as numerically-measured time pushes onwards, and one’s skin slowly sags downwards, somehow one hasn’t merely become ‘stuck in a moment’, but that the moment has terraformed, re-landscaped the horizon so that the next step beyond this ‘stuck moment’ seems to have never even existed, and that the places that proclaim to have movement are merely just full of frenetic ghost-like actions, speeding up but going nowhere. The unending nature of the sentence I have just written embodies a unending struggle to put to sleep the ghosts that haunt me. After countless debates around this matter, myself and John Wright began an investigation, of intertwined stories (personal to me) and wider post-millennial cultural moments, that we aim to turn into a solid body of work under the umbrella title The (Un)realised Project.

Thus far it has been agreed on that one specific work, The Mary Celeste Project (The Scene of The Crash), will take centre stage within this body of work. The Mary Celeste Project (The Scene of The crash), completed in 2014, uses my own turf (post industrial areas stretching along the foothills of the Yorkshire Pennines) to examine near pasts, lost futures and dead dreams to understand the wider contemporary social condition. Focusing on two lost futures and the un-locatable present, the condition of which is largely caused by the loss of the previous, and their haunting presence. The first lost future is that of popular modernism, which died in the latter quarter of the 20th century. The second lost future being the naively optimistic early to mid-1990’s, and its utopian gaze toward the coming new millennium. The un-locatable present here refers to a specific intensification of life under digital capitalism, looking at a severe disconnection to the passing of time since the 2008 financial crisis. The Mary Celeste Project (The Scene of The Crash) is crucially inspired by my sense of a loss of narrative and of being out of time, amidst a feverishly neoliberal reality. But certain locations I spent time in prior to the beginnings of this project were crucial to reasons behind making of it.

Ground-Zero Greenwich

It is clear then that specific geographical spaces are very important to this whole investigation. Thus, with the rarity of two people from northern England planning to embark on the south at the same point, it was essential we had to go another very symbolically important location: Greenwich.

So what makes Greenwich so important? We’d arrived in darkness, and the specifically-threatening-looking silver Met police cars guarding the gates put us off trying to find a way in, so we circumvented Greenwich Park wall right down to the river. One point of agreement on that walk was pivotal to the whole text I’ll write thereon after: my ‘stuck in a moment’ fixation with a 3 month (yet 3 year-long-feeling) time spent in London, unsuccessfully trying to complete an MA in Cultural Studies just down the road in New Cross, prompted John Wright to say to me (in a supportive manner, of course) that I really ought to have done the MA in Leeds (I had considered doing the MA at the University of Leeds, the institution John had recently been awarded an MA qualification at), but we both instantaneously and almost simultaneously responded by agreeing that I had to go to London; that there was something much larger and important at play.

I’ve written way too much already about the mental state I found myself in down London that forced me to leave, and the time leading up going and the time afterwards is far more crucial to the project and the reasons for the usage of my experiences within Greenwich. However, there is one crucial line explaining my state down there that activated this entire project: I believed I’d reached a total dead end, that there was nothing beyond this spell in London.

During this 3-year-disguised-as-3-month-spell, I found myself at Greenwich quite a few times (even ending up with a part time job there, just a week before finding myself back in bed in the north), finding the momentary ease under the autumnal ‘avenues all lined with trees’ an embodier of the wish for a granting of indefinite residence in a place I never really wanted to leave – “I like it here can I stay?” as the lyrics from The Smiths’ Half A Person that weaved through all other thoughts within my room in nearby New Cross.

Something had occurred here to a degree that I was finding it incredibly hard to get out of bed in morning after 15 years of habitually getting up at 7am. The years preceding had seen a building up of both foreboding and understanding of the global cultural situation, to which 2011 felt like the zenith; a clicking into place of a new reality from which we couldn’t go back. And now I was here, in the last 3rd of 2012, and it truly felt like the eye of the storm; the “that’s exactly it!” masters course (that I wanted to last forever, not 1 year of pressurised performance); the financial epicentres seen from my windows; the potential of meeting the world in a world-city; THE HEART OF DARKNESS – as it really did feel like I’d finally found it in as if in an inversion of Joseph Conrad’s novel – because, as comical as it sounds, the plentiful Megabus trips down there looking for a home were symbolic of a wider feeling of being worn right right right down into a man in search of a resting place. And, after the year 2011, there appeared to be no way of going back. And at that initial point before it all went wrong it didn’t matter that there was no way forward.

But as the London-endeavour lead on it became unavoidably clear that there was a dead end rapidly approaching. Throughout the preceding years there had been so much effort to show how entangled my inability to perceive a future for myself was with the dead end that was the endgame of the course the world was taking, to the point where I was exhausted just as it all seemed to come to a head. But as I walked around Greenwich, a place arguably unsurpassed in symbolic importance to creation of the world as we know it, to the extent that it often feels like the meridian was the first line ever laid, it became very clear to me for the first time how our ‘always on’ global capitalist culture was trapped by the past.

Greenwich is a place symbolically laden with traces of ghosts from other eras that refuse to die; a fusion of what-might-have-been’s (lost futures) and unshifting-has-been’s’ (archaic tombs that won’t close up). One that caught my attention was the Queen Elizabeth Oak, an important tree for the Tudor dynasty (a crucial period in the formation of Imperial expansion and modernity). Yet the tree is 100+ years-dead, and has laid on the floor like a wooden carcass for some years now too. Trapped under the weight of the past, with no future to speak of, the speed of life/the ‘always on’ endless labouring within the infinitely accelarating capitalist technosphere, traps us in a frenetic eternal-now epitomised by the Non Stop Inertia project. But in such a Stuck Record state, the present is also a void without a perceivable future in its wake, meaning the past, especially the near past, seeps into the void left by the unlocatable present (think of how traces of the optimistic 1990’s seem to cling to everything); impounding the pressure between the new reality demanded in the wake of 2011 and the lack of ability to be able to even think beyond the current moment. This is well and truly an hauntological state, and through my endeavouring after abandoning London to engage on a cognitive level with the South/West Yorkshire landscape I lapsed back into, these past 2 two years have been profoundly hauntological; all that has followed as felt unrealised…undead.

Connections….Always Looking for Connections…

Of course if we didn’t deem all this crucial to some wider situation we wouldn’t have embarked on the (un)realised projects investigation, nor would we have bothered taking the bus to Greenwich on a cold, dark night. The very fact that I also ‘sound like a stuck record’ on this blog now is more to do with my emotional energies smashing against 4 walls, looking for a way out, than the indulgences of dwelling in the past. Or at least this is what I tell myself. I have to tell myself this, because I am profoundly sick with the way things are, and the conviction that I am not alone means that the current direction of my work is as much as political act as the works I made in my early 20’s that dealt specifically with the threat of climate change.

The closed brackets around the ‘un’ in unrealised, was John Wright’s idea, positing it as the hope that all that is hanging around in a ghostly form will one day be realised. Using Jacques Derrida’s differentiation between an Ending of something and a Closure of something, John and I discussed how this dead-end feeling doesn’t have to be (or at least shouldn’t have to be) the end in itself, but a closure of something that allows the beginnings of another. Of course, our usage of specific geographical locations was a way of simultaneously commenting on this as both a deeply personal and deeply global cultural state. Perhaps using landscape is one of the strongest methods or articulating the fusion of two issues that would appear very distinct on a surface level?

.

The Utopian Never Truly Dies

As much as we felt it necessary to travel to Greenwich after our performance on the Saturday, after our final, most exhaustive, performance on the Sunday, we deemed it necessary to spend time in the Barbican complex before we set off back for the train.

There is something truly special about this place, which gets beyond the facts of why it remained like this whilst other Brutalist utopian residential schemes failed drastically; that this estate was designed for the well off, the cultural elite, and thus corners weren’t cut in its construction (nor was it fucked up socially by mass job losses), is a seperate matter to to truth of the place which is that it exists as a realisation of the utopianist society that truly could have been. This place doesn’t even seem to have been bothered by the onslaught of Thatcherism; neoliberalism seems to have been kept at the gates of this fort-like-structure, and you can imagine the same being true in long night of fascistic, repressive governance if we don’t find a way of changing the course we are on. It may be a place of the communal/the shared for those who already have their fair share, but in that it actualises elements of the ideal, it shows that they could, and should exist elsewhere.

What I like about this place is what makes me realise that as undead as I often feel, as emotionally-turned-to-stone as I regularly feel, I am still deeply utopian. Utopian is different from a Utopia; arguably Utopia can never exist, but to be Utopian is to be an idealist in life, not to accept any given reality as ‘the way it is’ – such fatalism is dangerous, and has arguably made the situation we are in profoundly worse to deal with.

The Barbican reveals traces of the utopian in the past that was left behind when neoliberal economic theory and postmodernism galvanised the TINA (there is no alternative to capitalism) reality. We sat in the canteen (the only place I know of in contemporary life where the word canteen isn’t associated undesirable eateries), and just sat, without the need for more pleasure-seeking, drink, etc – just sat. As we moved on toward the station, making a closure on this situation still felt as far off as it did before the performance, in the Barbican we did at least get a glimpse of elements of a place that could exist beyond this stuck point. This point has to be moved on from; personally speaking, I cannot stay here any longer.

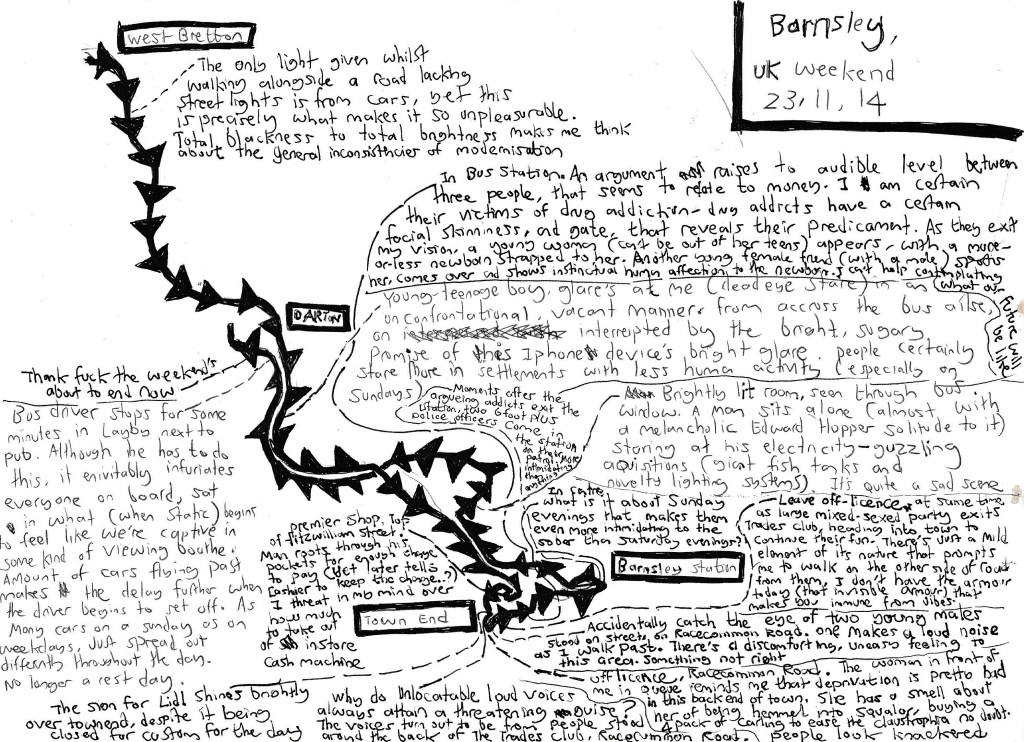

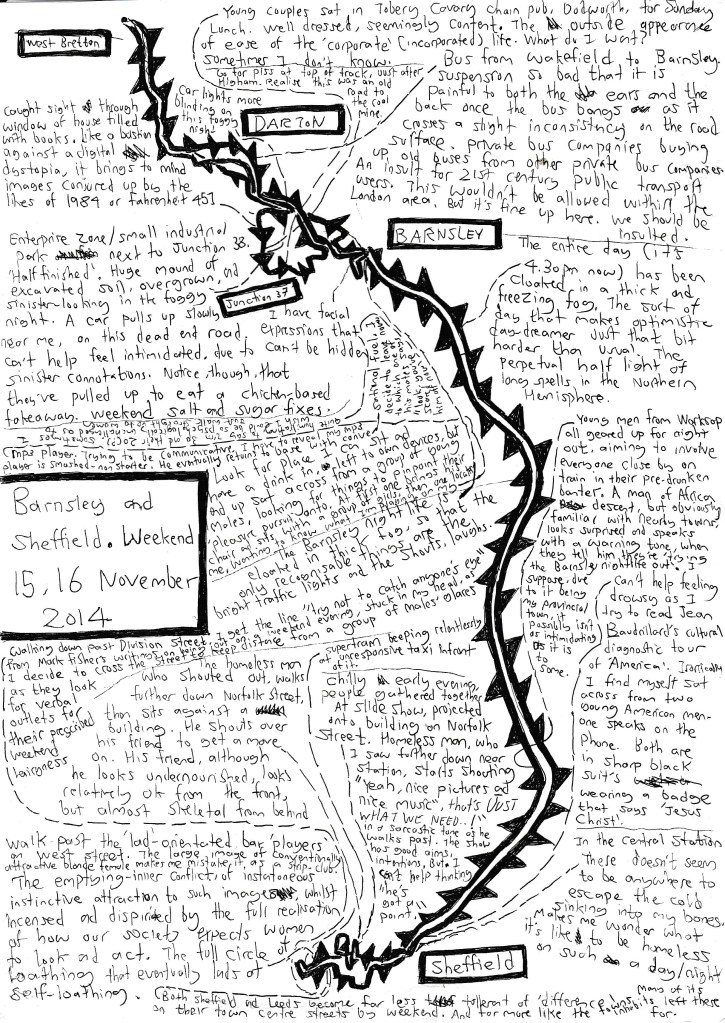

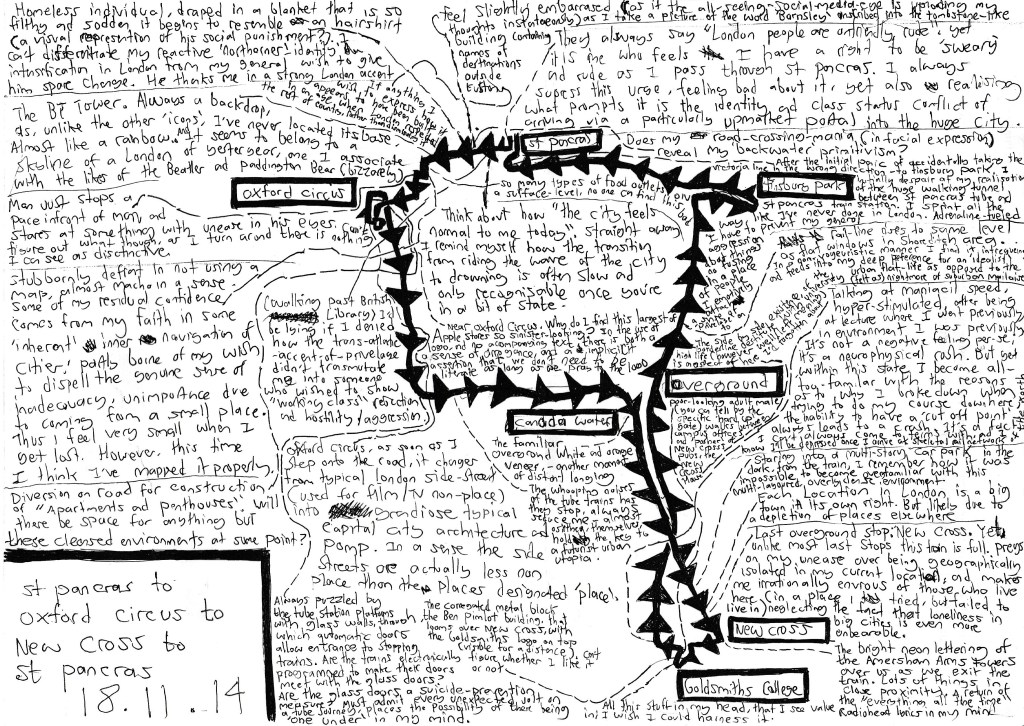

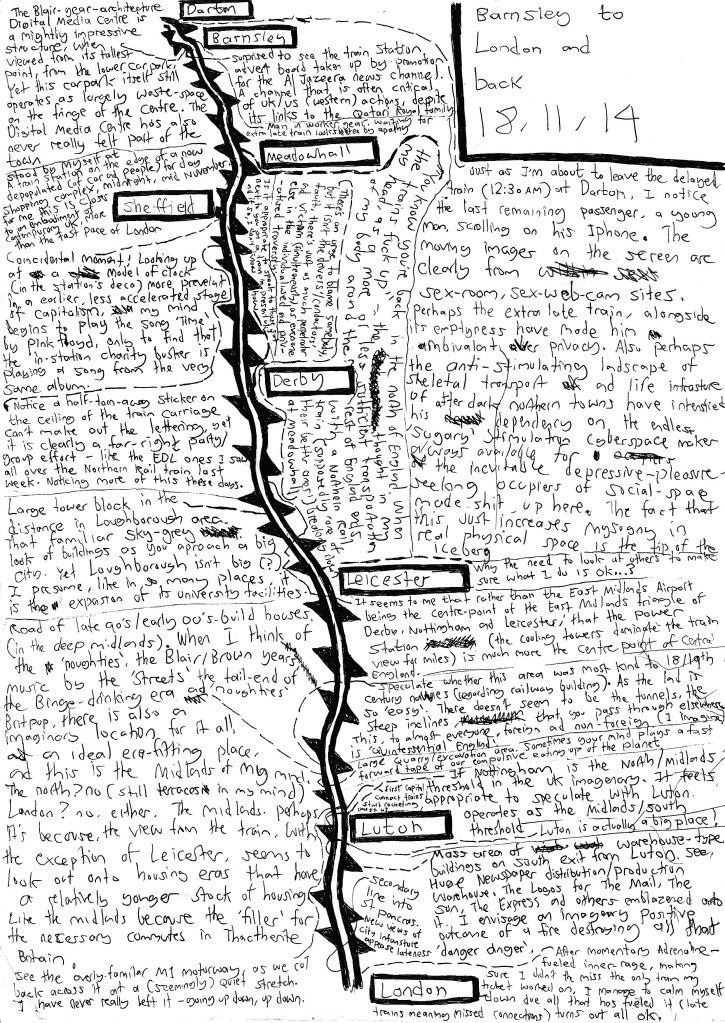

This is the 9th and the final post of 2014 in a series that I still call psychogeographical maps (or cognitive mapping). Quoting certain sections and using a selection of photographs to widen the project, which at its core still has the intention to be a Cognitive Mapping of Now – aiming to be useful for locating the wider socio-political mood, and the psychological impacts of it. This project has been ongoing since 2013 and has largely been an artistic response to Frederic Jameson’s 1990 essay, and call to action, Cognitive Mapping, which is posited as a means of class consciousness in our contemporary social landscape. Arguing that the “mental map of a city [I’d say the wider human-made landscape] can be extrapolated to that of the social and global totality [one that we] we carry around in our heads in various garbled forms”. Also, due to often residing in places deemed culturally ‘insignificant’ I feel that my work is justified by the words of social Geographer Doreen Massey in that “…spatially, the local place is utterly implicated in the production of the global and the globalisation that we so often find ourselves wanting to confront”. Although some of these maps aren’t made in places I live in, whilst traveling through them I am implicated and involved in that locality and the myriad of circumstances and incidents that constitute it.

The project has also allowed me to bring my love of maps into my art.

16 December 2014

“Always surprises me when I suddenly come across steep inclines in London. Like rivers (excluding the Thames), they are features that just don’t seem ‘natural’ in London as it stands. The place is such a concrete+metallic machine in its own right, that you don’t expect rivers and hills to start forming until you’re beyond the M25.”

“A fashion store on Kingsland Road, that looks [to be] webbed into some local scene. A single trainer shoe is on a plinth in the window. An area that presents itself as ‘against the grain’ [is] evidently as slavishly obedient to the consumerist reality, as anywhere else that is deemed less ‘edgy’.”

22 December 2014

“An unavoidable sight amidst the emotional chaos of the Xmas/New Year period: people, half drunk, coming very near to fist fighting, in Peel Square [Barnsley]. A young man VS the rest of the group, [he then] drunkenly storms up Peel Street, before leaning, with his head held low, against the window of the Iceland store. Next time I look he’s disappeared again.”

“Lots of teenagers stand amidst the now-empty market stalls, almost in complete darkness (I’m sure the streets lights are being dimmed or being switched off completely) [in Peel Square]. They look like they’re waiting for something to happen. But isn’t this more likely to be [the usual] sign of the state of [existential] boredom?”

24 December 2014

“Despite it being the most depressing of signs of our (collective) inability to look after the environment (and the moronic nature of the act), there is something visually appealing about about sites of fly-tipping. After all, the entire UK landscape is shape humans have made it into – this just adds another historical layer”.

“Make the mistake of trying to take a shortcut through the woods at the bottom of Litherop Lane, in order to get to path leading to Bretton Park. I realise something isn’t quite right when all the footpaths begin to fold back in on one another, almost like a race track course. A man stands looking at me. I [then] realise that the rumours that this is site where people meet up for outdoor sex are well founded. As I turn and head in the other direction from the man and notice the floor is littered with the left-overs of things used for sexual intercourse, I notice another man. As I find a path heading out of the woods in the right direction, I notice that he has been staring at me for a long period of time. It initially intimidates me, as it does when a stranger is staring at you in a bleak winter woodland, but afterwards I see it in a tragic light. Not that I am one for tradition, but to be stood there in a cold, muddy wood on Christmas eve, desperately waiting for sex, is a sign of the impoverishment of life’s larger wealth. These people are [more than anything] victims, addicts to a nihilist landscape. prisoners to the pleasure-pursuit.”

24 December 2014

“All the talk: that something big/a seismic shift from the current state of affairs is bound to happen soon, takes on an ominous feel within this eerie-looking early evening, which doesn’t settle easy with the [East Leeds] landscape through which we are witnessing it.”

“In the Dark Arches, walking above the river [which is at its] winter torrent levels. something awe-inspiring, specifically due to how if you were to fall in you wouldn’t stand a chance. These rivers are almost the hidden powerhouse, both past and present, of cities. I say ‘hidden’ because the common image of the river in the contemporary city landscape is as an appendage for pleasure for urban professionals – as if the river itself had stopped flowing in the ‘post industrial times’.”

27 December 2014

“I flare up inside at gawping [at me] passengers going around junction 38 [of the M1]. I realise that my year has been stained by bubbling anger. A deep frustrations with things that I cannot deny, but worry what will become of it as time moves on. Something must change. And maybe I’m not the only one harbouring this deep frustration with things?”

“A sharp turn in the road at the top of Woolley Edge serves as an analogy for a desperate need to change course in life – after a dead-end-style unenjoyable binge-drinking night in Barnsley, and my 31st on the horizon. But,as with every year, the question still remains “but to where?”.”

How the command to have perpetual good times causes its opposite

During the time I have kept this blog I have found myself annually writing a pretty messy and uncontrollably pessimistic piece around this time of the year, usually titled Crash-Landing of One’s Life at The End of The Year. This year [yes!] “to save me from [fucking] tears, I’ll try pre-emptive action, by getting to the source of the tributary that leads to Lake Breakdown. I have struggled around this time of year for as long as my post-millennial-mind can remember, yet what always makes it doubly hard, is that doesn’t feel like it is allowed the voice it usually carves slowly but surely out of the late-capitalist landscape. I know I’m not the only one, maybe even within the many, yet the banishment remains in place. As my mind labours throughout the day on this, blowing hot and cold, the words “Sharing the Pain” are repeatedly reiterated in my head, as a means of articulating what I mean in the face of accusations more or less inciting I take a pleasure in pessimism. I get to the point whilst I’m walking from place to place where I’m internally screaming “yes, sharing the pain is what is crucially missing” in our contemporary situation.

In a BBC Radio 4 documentary from 2013 commenting on the 25th birthday of the “wonder-drug” Prozac, Will Self argued that we shouldn’t be trying to be happy all the time that “[M]aybe the world is a difficult and abrasive place and hard place, and we’d be better off as a society if we acknowledged it in some way rather than papering over the cracks [and we] shared the pain”. The title of the documentary was [a] Prozac Economy, and maybe Prozac is emblematic of the implicit dictum of late capitalist society to be happy and living life to the full, 24/7. After spending 3 quarters of my 20’s on another brand of anti-depressant, I became convinced that what was often mistaken as/and resorted to by patients/customers as a solution to a genuine inability to function in life was actually the ‘papering over the cracks’ of all the things that were inconvenient to the command to be fully active, well-rounded, happy subjects in the ‘game of life’. What is being referred to here, isn’t even the massive cause for ‘pleasure-depletion’ caused by the expanding trail of ‘externalities’ (poverty, pollution, violence) sweated, and spat out by capitalist growth; what is being referred to is the banishment of the bad-to-mundane parts of life from the social lexicon. Good times and success have come to mean the same thing and an implicit command to be living life to the full glares at us from the workplace, street, and living room, making for an unending sensation that our lives are somewhat lacking.

“Life tends to come and go. That’s OK as long as you know”, I Won’t Share You, The Smiths

The Smiths/Morissey’s lyric on their final song of their final album from the late 1980’s almost seem to be wise words of warning for the increasingly USA-like consumerist landscape that the UK would increasingly exist as in the two decades following on, that life isn’t always full and memorably-great. Yet we now live in a social landscape drunk on expectation that life should constantly flow and never ebb.

But without going much further just yet, in comes the emotional-stomach-pumping that is Xmas/New Year; a annual occurrence that is more of an unwritten consensus for a time of mental illness more than anything. Tears, relationship breakdowns, taxi-rank travesties – a general unhinging of minds. It’s like being sucked into a black hole; you have to make plans well in advance to ensure your coordinates are on course to steer you way past its gravitational pull. Most of us fail to do this, and just have to hold on in the best psychological state we can until we come out the other end in early January. It disorientates, messes any routines we have that give us scope for making (some) sense of things; giving us no means of coming to terms with the burning sensation “why aren’t I having a good time? I’m supposed to be. What the hell do I do now?”.

Many of us (usually referring to some unfortunate other – but often meaning ourselves) talk about how Xmas/New Year can be a ‘lonely time’. But I don’t think it is actually that much to do with being alone at this ‘special time’, but more a loneliness induced by this omnipresent command to be ‘living it up’. We feel more left out, missing out, with a need to be having good times-max for 2 solid weeks – no wonder we feel so exhausted by the end of it. This pressure to be constantly sociable, in the thick of good times, coincides with the increasing atomisation of human beings, due to an increasingly presence of market forces coming between al human interaction, so much so that George Monbiot wrote a recent column calling this “the age of loneliness”; both our real and imagined loneliness have increased.

My interpretation of the usual defence of Christmas [specifically, regarding the UK], as an ancient tradition of good will in the deep dead of winter, is that the difference lay not really in loss of belief in the Christian story (or tradition), but in the shift from it being a time of bringing good will, and an easing of pain, to a time where the language describing pain and general not-good times is banished from the existence. A burgeoning feeling of unease, makes us feel more distant from the (seemingly) joyous crowds. But my suspicion is that most of that crowd are actually only connected by their hidden loneliness.

Perhaps this shift can be placed at a point within the 20th century when a newly emerging stage of capitalism (a more completely market-saturated, market-dominated and deterritorialised society) snatched the mores (the demands/actions for the liberation of pleasures, freedoms to enjoy life) from the cultural revolutions of the 1960’s that fought to overthrow a previous style of capitalist domination. The counter-cultural liberation of the human soul in the mid-to-late 20th century turned out to be like rocket fuel to what could be called an emerging hypercapitalism, that re-appropriated and ventriloquised it so well, that tracks like the Velvet Underground’s All Tomorrow’s Parties becomes a slogan for this different style of domination.

Many theorists have worked hard to interpret this crucial shift, usually located in the 1970’s-80’s, but most notably Gilles Deleuze. Deleuze’s essay Postscript for Societies of Control, using Michel Foucault’s description of societies of Discipline and Punish (“operating in a time frame of a closed system”, based on containment and territorial in nature) to delineate the previous form of domination, talks of the beginnings of a new form of domination by “ultrarapid modes of free-floating control” where the “corporation has replaced [the older model] the factory, and the corporation is a spirit, gaseous”, it extends into all walks of life and “constantly presents the brashest forms of rivalry as an healthy form of emulation that opposes each individual against one another, and runs through each, dividing each within”. We are no longer citizens and workers, we are competitors and consumers; enforced individualism. (Digression slightly, but being as I am referring to many bands here, I will argue that the quintessential record for a discipline and punish society is Pink Floyd’s The Wall – released at that crucial point, 1979, when the transition was truly occurring, and that the quintessential record for control societies is Radiohead’s 1997 pre-cyberspatial-horror record OK Computer).

And, In a simplified way, it would seem that what the revolutionaries of the 1960’s were trying to overthrow was the discipline and punishment stage of capitalist domination, unfortunately oblivious to the more gaseous ‘control society’ stage of capital that was de-territorialising the sources of power, and re-appropriating the energies pitted against that older form, at the time. Unlike in a society based on discipline and punishment our pleasure drives aren’t something to be kept in check from a watchtower, but something left to the management of the individual, whilst advocated as a consumer rite of passage. As Zygmunt Bauman wrote in his essay The Riots – On Consumerism Coming Home To Roost, the 2011 UK rioters were ‘disqualified consumers’ who were (financially) unable to carry out their ingrained duty, and thus the rage of injustice was followed by the return of the repressed rite of passage to consume/enjoy – thus came the looting. Because control societies are always losing control, from the macro-economical right down to individual level.

What has all this got to do with Xmas/New year though? Well, all the factors that drive our contemporary reality, hit a huge power surge at this point every year; as Xmas/New Year now operates as some kind of social nervous breakdown, from which it rises back out in vain with redemptive plans for the new year. All the cities in the UK, by weekend, transform into landscapes of people desperate in pursuit of pleasure, in what is still seen as ‘leisure time’ – do they find their fun? Maybe eventually. Christmas however, is this on overdrive, when we truly do become lonely prisoners to the pleasure pursuit. ( The Black Friday escapades, that are condemned by those who foolishly think they are exempt from consumer subjectivity, are if anything a mirror image of the London Riots).

I don’t believe the pursuit of pleasure, and the unrealistic expectations we become condemned to place on such periods deliver their promise at all (In all honesty, the best nights out I have are ones that come out of nowhere, usually when you bump into a friend whilst out on a mundane town centre stroll). The failure to find pleasure on a singular weekend night out can be shrugged off far more easy, but the command to be fulfilled around Xmas/New Year can bring about series mental distress.

There is no way to go much further than this when the most crucial thing (on my part) is getting through the period with minimal damage as possible. It’s fair to say, I think we’re all swept along (or pulled under) in the tide of society at different degrees. At least I’m being honest in saying I’m far more seduced with the perfume of aspirational hyperbole than I’d ever wish on anyone else. It’s like a sealed pocket that releases its poison at certain points throughout the year.

I truly believe if ‘sharing the pain’ was a dominant paradigm, in the place of ‘everyone must enjoy themselves’, life would be truly more easy. It is impossible for a society to share the pain, and accepted the difficulties of life whilst there is a command to be a ‘player’. I also feel a society that acknowledged the difficulties of life would find it easier to adjust to adverse scenarios, rather than responding to it like the infantile consumers it currently moulds us into; to consume and suffer in silence.

This is the 8th post in a series that I still call psychogeographical maps (or cognitive mapping). Quoting certain sections and using a selection of photographs to widen the project, which at its core still has the intention to be a Cognitive Mapping of Now – aiming to be useful for locating the current socio-political mood, and the psychological impacts of it.

UK Weekend 15/16 November 2014

“Chilly, early evening, people gathered [for] slideshow projected onto building on Norfolk Street [Sheffield]. A homeless man, who I saw [asking for spare change] further down towards the station, shouts “yeah, nice pictures and nice music – that’s JUST what we need!” in a sarcastic tone as he walks past. [Even though my own art is featured in the projection] I can’t help thinking “he’s got a point.”

UK Weekend 15/16 November 2014

“Chilly, early evening, people gathered [for] slideshow projected onto building on Norfolk Street [Sheffield]. A homeless man, who I saw [asking for spare change] further down towards the station, shouts “yeah, nice pictures and nice music – that’s JUST what we need!” in a sarcastic tone as he walks past. [Even though my own art is featured in the projection] I can’t help thinking “he’s got a point.”

“Enterprise Zone/small industrial park next to junction [37]. Half-finished. Huge mound of excavated soil, overground and sinister-looking in the foggy night. A car pulls up, slowly, next to me, on this dead-end road. Can’t help feeling intimidated due to sinister connotations. However, I noticed they’ve pulled up to eat a chicken-based takeaway. Weekend salt and sugar fixes.”

18 November 2014

“Feel slightly embarrassed (as if the all-seeing-social-media-eye is uploading my thoughts instantaneously) as I take a photograph of the word ‘Barnsley’ inscribed into the tombstone-like building, [that lists] the names of destinations outside Euston/London. If anything, I wish[ed] to express how it appears to have been built/engraved in an age when London respected the rest of the country, rather than dismissing if [maybe].”

“[At New Cross Gate Station] Talking at maniacal speed. Hyper-stimulated after being at a lecture where I went to study [once], in an environment I was in previously. It’s not a negative feeling, it’s a neuro-physical rush. Yet within this state I become all-too-familiar with the reasons as to why I broke down when I tried to do my course here: the inability to have a ‘cut off point’ always leads to a crash. It’s a fact I can’t always come to terms with, and I know I’ll be depressed [later on] once I arrive on the ‘skeletal’ rail network of the north.”

“[Row] of late 1990’s-early 2000’s-built houses, in the ‘deep Midlands’. When I think of the ‘noughties’, the Blair/Brown years, music by The Streets, the tail-end of the ‘binge-drinking era’, noughties ‘britpop’ [and the Iraq war as background noise], there is also an ideal-fitting location for it all, an era-fitting place. This is place is the Midlands of my mind. The North? No (still [older] terraces in my mind) London? No, [I think London is Now]. The Midlands. Perhaps it’s because the view from the train, with the exception of Leicester, seems to look out onto a landscape of [the last mass construction of – private – houses, in the boom years of New Labour]. The Midlands looks of younger housing stock. Perhaps it became the ‘filler’ for the necessary commutes in Thatcherite Britain[?].”

“Just as I’m about to leave the delayed train (at 12:30 am) at Darton, I notice the last remaining passenger, a young man, scrolling his Iphone screen. The moving images on the screen are clearly from sex-room, sex webcam sites. Perhaps the delayed train, alongside its emptiness, have made him ambivalent over privacy. Also, perhaps the anti-stimulating landscape of skeletal transport and life infrastructure of after-dark Northern towns have intensified his dependency on the endless ‘sugary’ stimulation that cyberspace makes always available for the inevitable depressive-pleasure-seeking occupiers of social space-made shit, up here. The fact that this just increases misogyny in real physical space is just the tip of the iceberg.”

19 November 2014

Sheffield

UK Weekend, 21, 22, 23 November

“[Sheffield Station] Water drips from Northern Rail Carriage, as everyone waits in haste for the doors to open. Two young men arrive in [sodden sports clothes]. [You can tell with some people that they’ve had a hard upbringing from their face-shape, their posture, and even their mannerisms]. They are drenched– only the poor get drenched in a rainy city. You never see the poor with umbrellas.”

“Peel Street often feels like the ‘Barnsley Badlands’. What I mean by this is that it feels like one of those locations where the fallout from welfare-eroding neoliberal economics [and the ideology it generates] is most acutely sensed. A one-time boulevard now in social disrepair – it almost feels more fitting to downtown America.”

“The Only light given whilst walking alongside a road, lacking street lights, is from cars. yet this is what makes it so unpleasurable. Total darkness to total brightness makes me think about the [gaping] inconsistencies of modernisation.”

“Brightly-lit room, seen through bus window. A man sits alone (almost with a melancholic Edward Hopper solitude) staring at his electricity-guzzling aquisitions (giant fish tank and novelty lighting systems). It’s quite a sad scene.”