WARNING: THIS WORK CONTAINS STRONG AND UNPLEASANT LANGUAGE ALL WAY THROUGH. THANKS

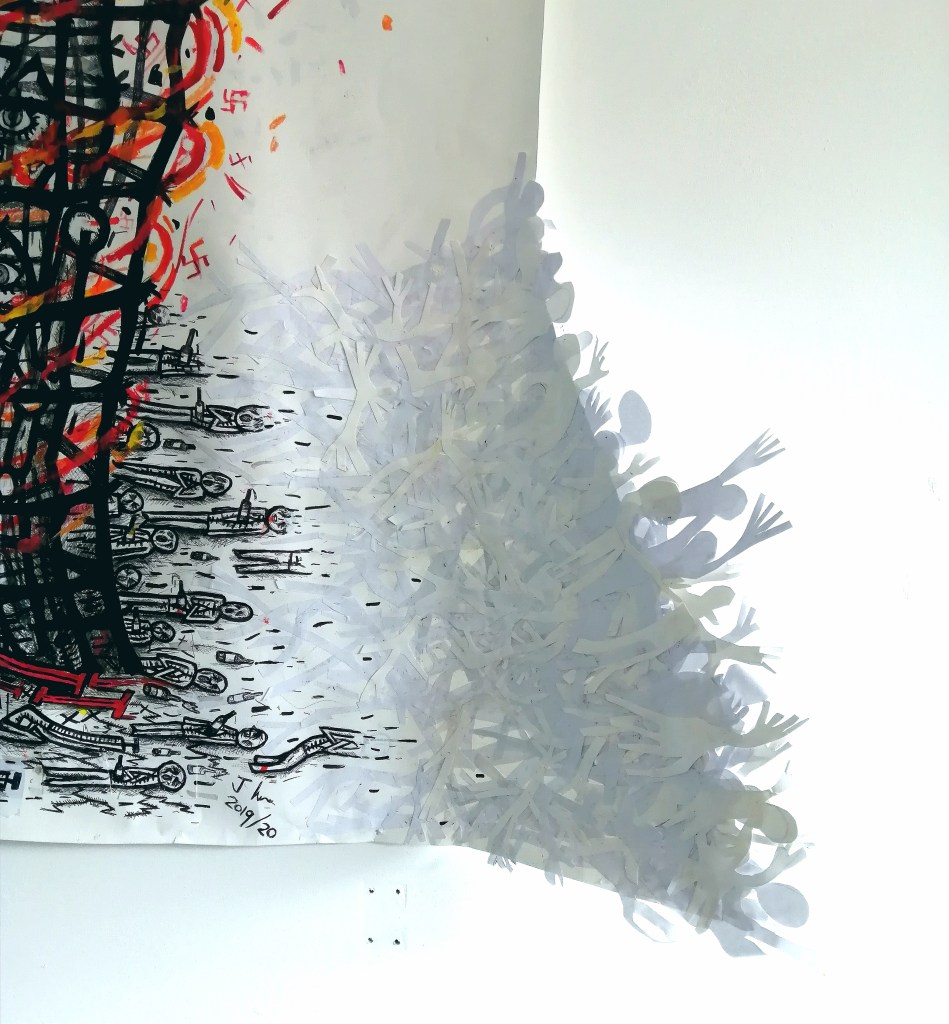

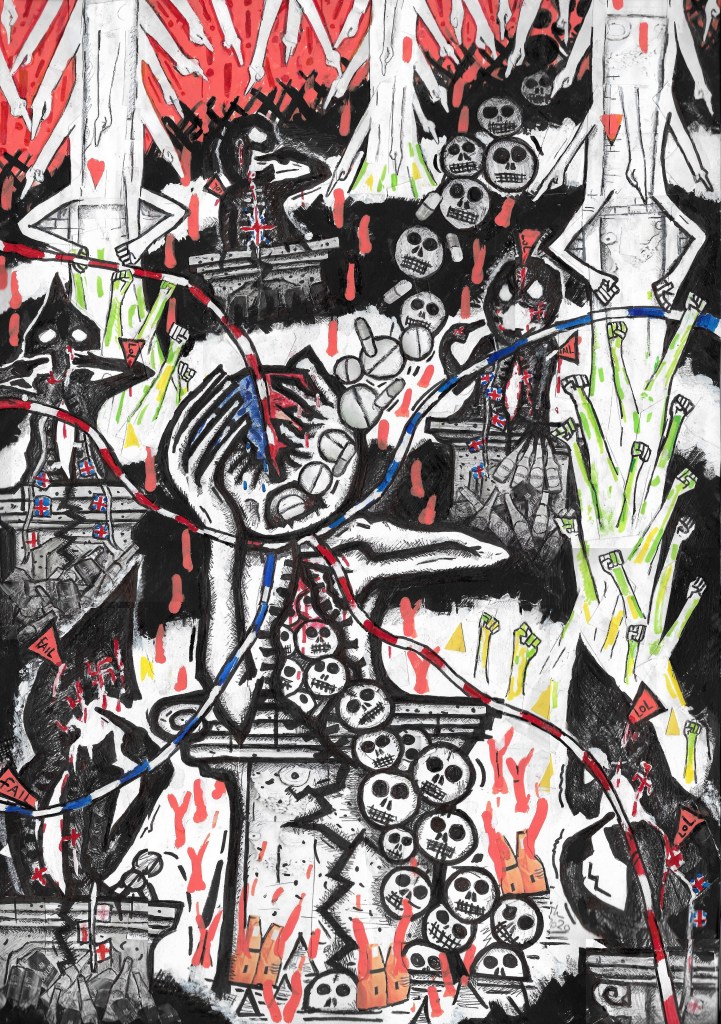

‘The Crucible of all our Traumas’

‘The Crucible of all our Traumas’

Mixed media on paper.

I decided it was best not to present this work with a formal ‘explanation’, as I’m hoping my next work will do the explaining. But I’m happy to discuss what it is about.

Been pretty intense trying put this work together, I almost ripped it in half at one point.

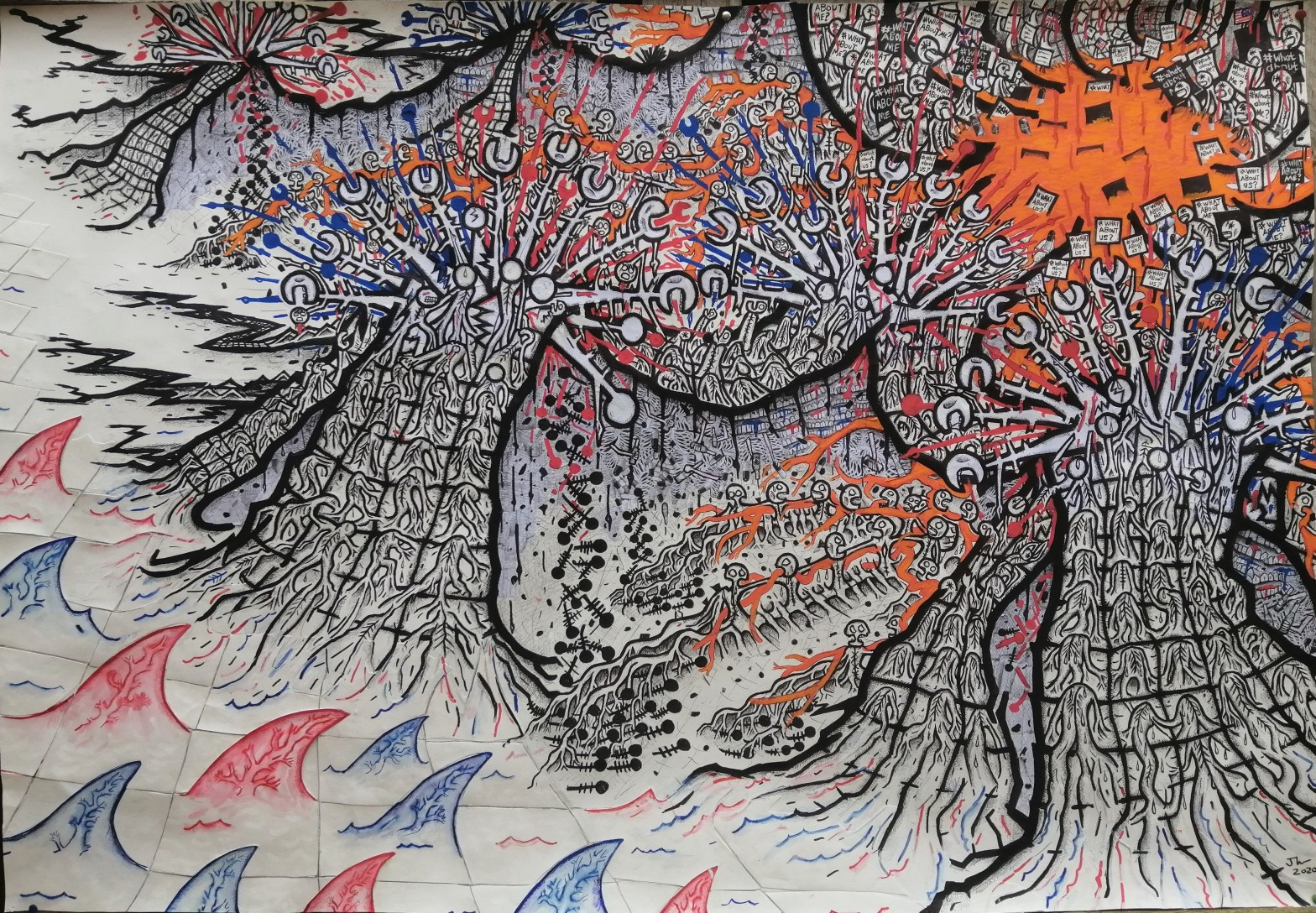

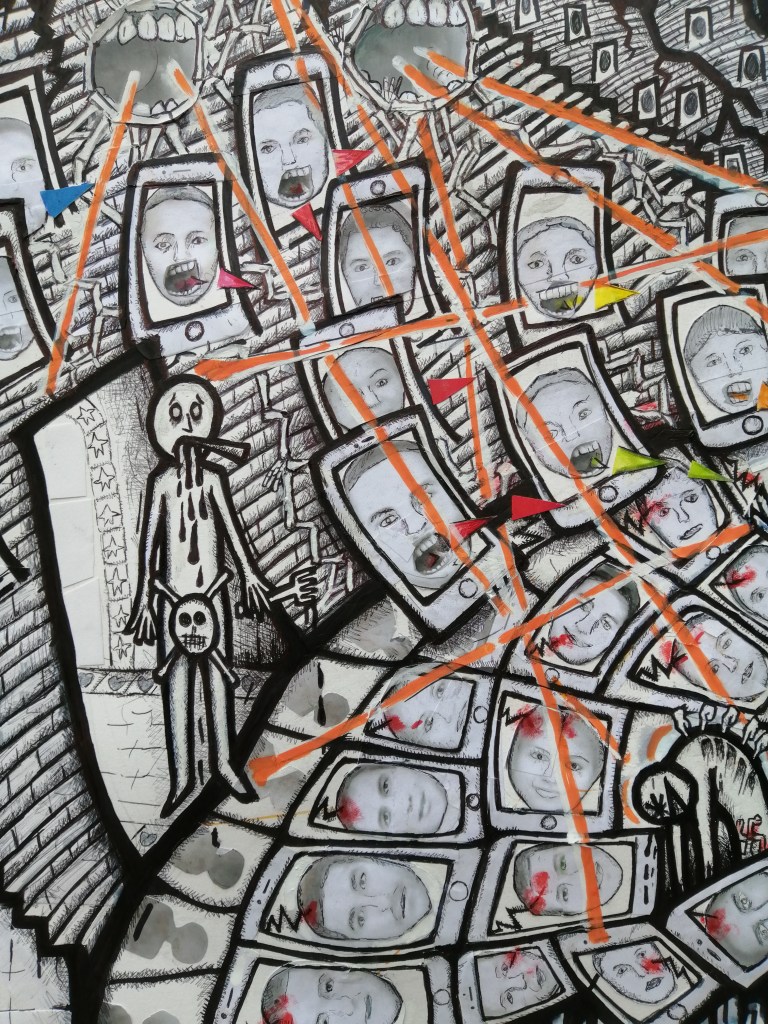

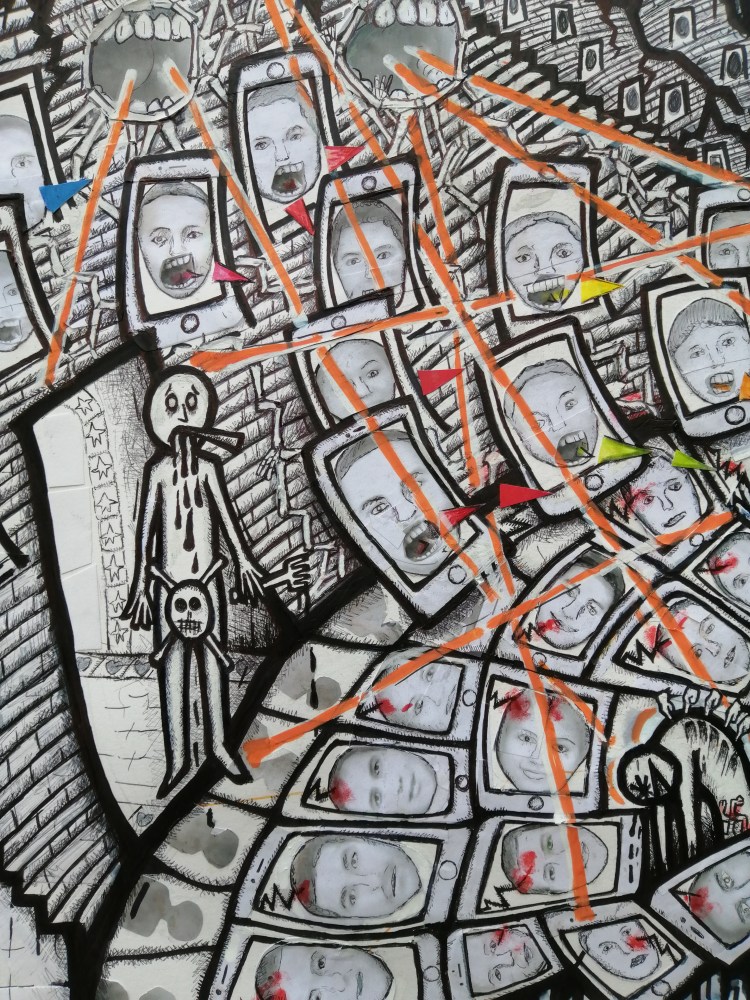

Self portrait during a culture war

(2020, mixed media on paper)

‘Self portrait during a culture war’. (mixed media on paper)’.

In a sense I think I’m making this work for social media, for our over dependency on it during a time of restricted physical socialising, for the way it is shaping physical reality the more we rely on it. I made “Self portrait during a culture war” trying to find a way to critique the increasingly dividing arguments within social media, in the only way I could think of: making myself the object of critique, in a drawing that exaggerates the contradictory, and often ugly, emotion-cum-identity ‘matter’ in my own ego make up.

It’s the contradictory stuff that all of us carry (?), yet that cannot occupy the same space at the same time in our current forms of communication, which make it hard for us to find language that doesn’t ‘corner’ us against another side.

I put a big emphasis on the contradiction between having strongly held desires for social change, and many reactionary elements. They are divided into blacks and whites (metaphorically not literally!) because they cannot recognise one another, and this makes them ever more extreme in their differences.

The progressive side tries to ‘teach’ the other side, but the more it does so the more the ‘other’ side becomes entrenched around the beliefs/feelings it stands accused of having. This is because the progressive side, in all it’s good intent, overlooks both the way language travels over a space like social media, and also overlooks the emotional wounds, pride, even humiliations (relative to that person’s social/historical experiences), which I believe are prodded when progressive language makes us feel guilt.

Equally, I think that one of the illusions seen through the prism of ‘identity politics’ gives us the painful impression that it is we, out of all peoples, who have been ‘left behind’/’not cared about’, which I believe is a shared experience that connects the majority of us beyond the idea of ‘identity politics’.

Again, to prevent pointing this finger at others, this is why this is based on an exaggeration of my own contradictory feelings, and the raging internal arguments that flare up upon encountering the crossfire of social mediation.

Drawing feels relevant again

After using drawing as the main mode of expression for my art for well over 10 years, a couple of years ago I just stopped. I didn’t stop making art, so to speak, but it felt like drawing, my way of drawing, had not only run out of steam, but relevance.

The reasons for this are plenty, and complex, and I’m happy to discuss them elsewhere, as they relate to a whole matter of things, but at the moment this would be a messy digression.

To cut a long story short, from September 2018 to September 2019, I worked on a film which was a fictionalised account of my own experiences. During that moment it felt like the last move I had left to make, if art was a strategy game. But in life, it felt like a gigantic full stop, from one thing to the next; for, despite perhaps it’s awkward introduction, when I finished ‘Wall, i’ I thought “that’s what I’ve been trying to fucking say for all my adult life!”.

It was a massive version of what all my drawings had always been: long meditations that would take me months to produce, and leave me (on a smaller scale) thinking the grass (of the none-artist) was greener on the other-side.

Now, every word that isn’t about the huge current global, societal issues, feels like it is walking a tightrope of accusations (the accusation of ‘privilege’ is a specifically prevalent accusation, as we can always see one for what they have, and we don’t, over our tech-mediated field of comprehension). But it has been precisely these current crises, in our streets, on our screens, and crucially within our inner dialogues, that suddenly made drawing relevant again. Suddenly it felt apt to try to finds compositions to depict the Now, through drawing. Yet, like always, I am a slow worker. So the works below are my ‘works for the Covid 19’ era, thus far.

1. A New Spring has Sprung.

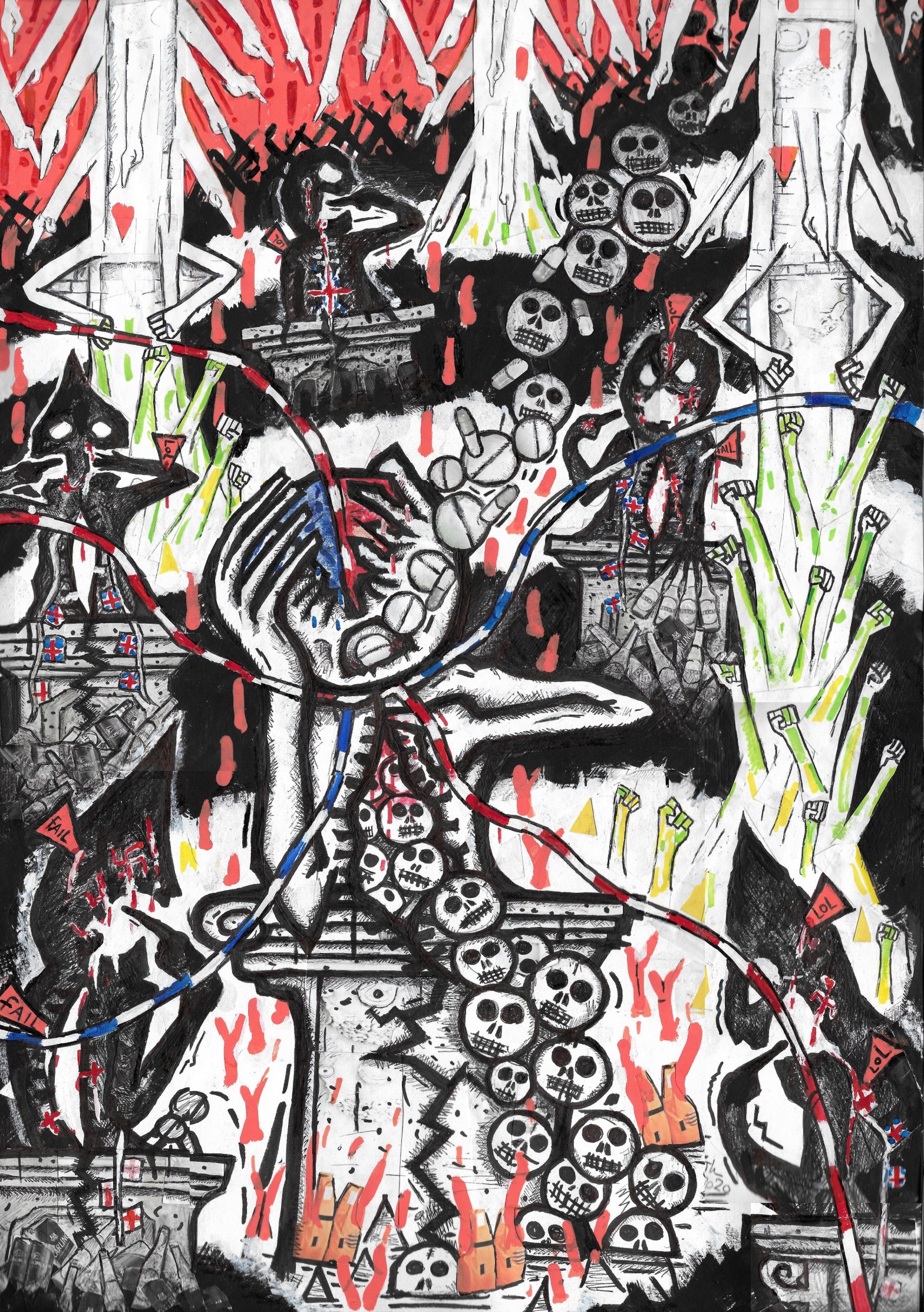

2. Nausea

3. All of Your Gods are Pounding my Head’

All of Your Gods Are Pounding My Head

All of Your Gods Are Pounding My Head (2020, mixed media on paper)

I’ve made another video introduction to this work. A work that I got into a real moral tangle about revealing right now, amidst current affairs.

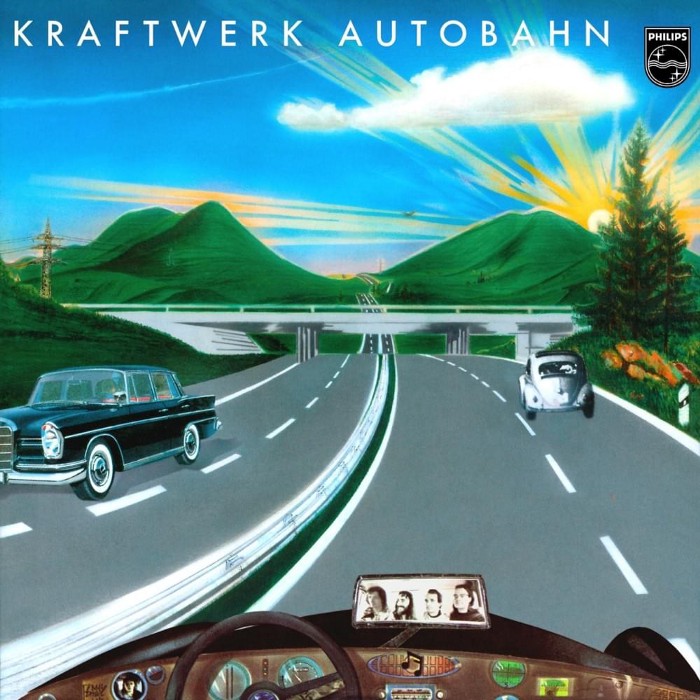

Kraftwerk in the time of Covid 19

This may seem like a ‘stretch’, but I argue that renewed interest in the music of Kraftwerk, brought about by recent passing of co-founder Florian Schneider, makes for strange resonances and recollections in a world partially suspended by the outbreak of Covid 19.

Now, I’m not usually one to share news of the death of a notable artist over Social Media, which often feels like an unending procession of obituaries. But, nonetheless, Kraftwerk had made a deep impression on my 21st century adult life, so I decided to start by playing one of my favourite tracks by the group, Ohm Sweet Ohm, from the album Radioactivity, driving on my way to work.

Driving, or at least commuting to work is an almost universal experience in 21st century life. If you haven’t fallen foul, ‘lumpen-like’, to the grossly uneven economic development of the past 40 years, it’s very likely you have to do it.

However, not today.

Normally, if you were to be commuting at 8:30am, you would be part of an unending flow, so immersed in the stop/start blockages, so very much part of it, that you wouldn’t even be able to ‘notice’ the motorway, the railroad, or the terminals. You’d most likely either be trying not to think about it, or you’d be overcome with thoughts regarding your destination.

But today, the motorway was almost exactly like it was as the once-brand new motorway you can see in the image above, from 1970; which, in turn, is very much like the motorway on the cover sleeve of the 1974 Kraftwerk album Autobahn.

Listening to Ohm Sweet Ohm whilst finding myself on a motorway with significantly less traffic than normal, joyously brought the music of Kraftwerk and the architecture of the M1 motorway together. For the first time in maybe over a decade, this particular synchronisation gave me a joyous ‘allure for the Modern’, and I try to explain why, now.

Although it’s clear the passing of Schneider has absolutely nothing to do with Covid 19, I believe that it’s given us an incentive to re-listen to Kraftwerk at a very appropriate moment: we live through a time when our use of the technologies, infrastructure, that uphold our ‘non-stop’ 21st century lives, have been partly-suspended, seemingly indefinitely.

In fact, I can remember the last time I felt this very joy in the ‘allure for the Modern’. It was on another relatively mundane node within of our hyperconnected world, as my local service train pulled into the Yorkshire hub of Leeds in the autumn of 2008: I was listening to Kraftwerk’s Trans Europe Express.

So what is this ‘allure for the Modern’? Why is it important to Kraftwerk, and why do I think our recent lives pre-Covid lost this ‘allure for the Modern’, and why do I think it gives us a chance to look at our world anew?

I’ll try to answer all this in a post I’ll do my best to keep as interesting and concise as possible.

The ‘Modern’ is arguably quite different from just living in ‘Modern times’. Or, to put it another way, the definition of the past 40 years or so, that we call ‘Post-Modern’ can be misleading. We are still in a world defined by all things ‘Modern’; the way we work, travel, eat, seek leisure, even the procedures around dying. These things have become more chaotic, far more intertwined and uncertain than arguably even for our grandparents and great grandparents, who were also ‘Modern’, and these changes are often what we’d ascribe to Post-modernity. However, I argue what mainly characterises these past 40 years is a feeling, or lack of: a loss of a sense that technology, and progress in general, are leading us to a far better world. The wonder at such technological achievements is what I call ‘the allure for the Modern’.

Chatting about Kraftwerk with friends with similar music tastes in the 21st century would culminate in an utterance that just didn’t feel right. Why would we agree that Kraftwerk’s music still sounded ‘futuristic’, 30/40 years on, in a world, that was, to all intents and purposes that very future to those albums?

I’ve already mined the ideas of theorist Mark Fisher way too much, but Fisher’s and the Italian thinker Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi’s idea that in the past 40 years we have witnessed a ‘Slow Cancelation of the future’, is still, I argue the most fitting expression of a strange sense that aspects of 20th century culture still seem more ‘futuristic’ than the present. Roughly identified as a cultural reality brought about by a synchronisation of shifts in political and economic life with the rise of computer technologies, it argues we can no longer imagine a world different from the present. For Fisher this change, that he said was most noticeable in cultural forms, especially popular music, was political, and he diagnosed our age as inflicted by a ‘capitalist realism’.

But regarding Kraftwerk, why were they so futuristic?

For a start, perhaps Kraftwerk’s futurism had to come from Germany? David Cunningham, in his essay Kraftwerk and The Image of the Modern, (featured in Kraftwerk: Music Non Stop) argues that Kraftwerk, along many other young German artists at the time, looked ‘back to the future‘, bypassing the black hole left by Nazism and the legacy of the Second World War, to look back to the Modernism of early 20th century Germany (such as the Bauhaus movement and the early Frankfurt School). But rather than looking back in a retro-fetish sense, Cunningham writes that “[T]hey [Kraftwerk] gain their meaning as modern from their dynamic relation to past works [my own italics], through a determinate negation of what precedes them…”

Germany along with Japan, upon unconditional surrender to ‘allied’ forces in 1945, were subjected to ‘the Marshall Plan’, a project to rebuild the nations and their economies after the war. Without going too much detail (their de-militarisation, and how being ‘victors’ also shaped the ‘victors’), it is clear to see that vast swathes of urban Germany and Japan were rebuilt in an ultra Modern style. Unlike the UK, for example, which politically, and physically, was able to maintain enough of its former self during the post-war rebuilding, Germany, for the large part had to start as if brand new. What I’m inferring is that, despite the great leaps in what Mark Fisher and Owen Hatherley call ‘Pop Modernism’ in the UK and USA, the conditions of Germany, and of being German, in the Post-war era, created the conditions to be ‘Kraftwerk’.

But what is it about our current Covid 19 life that highlights this ‘Modern’ (again)?

In an essay for the pop philosophy book ‘Radiohead and philosophy’, Adam Koehler writes about a band who perhaps, like Kraftwerk, make music that isn’t, as Koehler writes, merely ‘about’ the conditions of life produced by technological ages, but is an ‘artefact’ of it.

Koehler here, is making this claim about the music of Radiohead from the Kid A album onwards; how it isn’t “about [the] low-level panic and anxiety produced by living in “the information age”, [but is] an artefact of that information and that age…”

Koehler tells us that Martin Heidegger in his book ‘Being and Time’ says that the technologies that we depend upon for “our everydayness…retreat[] from our attention and becomes invisible to us” and that we only notice them when we don’t want to, when they break down, stop working. He says what makes the ‘anxiety or panic’ that domes Kid A…” so ‘familiar’ is that “we hear technology”, which is very different from simply using technology to make music.

Perhaps (especially within the 5 consecutive albums Autobahn, Radioactivity, Trans Europe Express, The Man Machine and Computer World) no other band has quite enabled to us to “hear technology” quite like Kraftwerk”. However, apart from an implicit melancholia that seems to haunt the otherwise upbeat rhythms of Computer World (that perhaps speaks more to a loneliness of 21st life than anything), we don’t necessarily ‘hear’ technology breaking down as in Radiohead. What we do hear is this ‘modern’ technology in a real world of Covid 19, where partial suspense of ‘everydayness’ has made the intertwined hyperconnected world upon which our ‘non-stop’ lives depend become noticeable, perhaps for the first time in decades we can “see technology”?

We can see the motorways, the railroads, we can see, arguably what remarkable feats of engineering and architecture they are, because we are barely using them. We can see the technology behind food distribution, for example, because, perhaps for the first time in our 21st century life, we have been forced, as a society, not to see it as an endless resource, originating from nowhere.

Covid 19, I argue has made the dust settle over our frantic lives of the past 40 years to settle. What the future holds is uncertain, by what it does is make visible ‘Modern’ infrastructural achievements that wowed our near ancestors, but has become invisible to us, immersed in it as we were until very recently. It is only coincidence that the passing of Schneider has brought Kraftwerk back to our attention during this pandemic. But, in this temporary space where technology is once-again visible, Kraftwerk isn’t just relevant again, but once again a deeply immersive, enjoyable experience, if you happen to be one of the fewer people using the our Modern infrastructure. It really does reactivate the ‘allure for the Modern!’

‘Nausea’

Nausea’ (2020, mixed media on paper)

Stylistically, this work could’ve been made 5 years ago, but I found it useful to return to certain ways of making right now…

A New spring has sprung

For the first time, probably due to the larger situation, I decided to make a video work about my latest piece of work. A New spring has sprung (mixed media on paper).

Wall, i

Precursor: I developed ‘Wall, i’ as a film intended for exhibitions, and independent screenings, but was encouraged to make it accessible online. The work covers a series of complex contemporary issues, so whilst the film is available to share, I just politely ask people not to share clips of it out of context, as, out of context it may unjustly offend (even in our are of stimulation-saturation!), So, please, share with consideration 🙂

‘Wall, i’, is a young male who is born into a world that tells him he can be whoever he wants to be, that the ‘old world’ of duty, discipline, division and drudgery has gone. Yet the promise doesn’t turn out quite how it was anticipated. In a new world of new technologies and self-help slogans, the past returns with anger, and ‘Wall, i’ becomes trapped inside himself. Unable to connect, he descends into a spiral of minor addictions, loneliness, bitterness and hatred, from which he ultimately seeks forgiveness.

A song-based film, Wall, i is a response to the 30 anniversary of the fall of The Berlin Wall, and the affirmation that we had reached ‘the end of history’, and the 40th anniversary of Pink Floyd’s The Wall (‘Wall, i’ tries to employ similar themes for a ‘Millennial’ experience). It is also an autoethnographical (using collated experiences personal and pier experiences, to expand into a fictional self) response to the political, social divisions we now see in 2019.

This film was a highly collaborative film, and I wish to thank everybody who helped. I could never have done anything like this without the help of these people.

Co-songwriter and music composer – Lee Garforth

Assistant director – Jordan Blake

Assistant director (2) – Sheldon Ridley

Lead actor – Ben Crawford

Lead actor and contributing vocalist – Jade Robinson

Lead actor – Laura Clowery

Creative support – Rebekah Whitlam

Editing support – Katherine Lacey

Support assistant director – Rob Nunns

Supporting vocalist – Carys Bryan

Sound editing support – William Addy

Technical support – Simeon Dear

Actors: Yew Tree Youth Theatre (Ben Walton, Chloe Walton, Ellie Barraclough, Madison Mersini, Lara Earnshaw, Lucy Gallican, Tom Mason)

Actor – Kevin Parkin

Actor – Mollie Hobson

Actor – Sam Francis Read

Actor – Celeste Taylor

Actor -Lucy Crouch

Event support- Chris Scarfe

Event support – John Chambers (Temple of Muses)

Event support – Steve Ellis

Supporting actor – Ben Parker

Supporting actor – Rose Merry

Supporting actor – Rachel Marie Thornhill

We Want to live

My recent show ‘A Eulogy for a Lost Decade’ in Doncaster, has been a really defining show for me. The exhibition brought together my film about identity, mental health, loneliness and other things in the Millennial generation (Wall, i) with a series of my drawings from over the past decade. I never realised that I was now looking at the end of a story, a life narrative, a sign to move on in life, to live a better life, with or without being an artist.

This means that the work that this recent and the first large scale drawing in over 2 years, ‘We want to live’ is not only a full stop and the end of all this work, it is now time to take heed. As the person I currently am, the ego ecosystem it sustains, I have said all I can say. The reason I made my film, which was very much about my own life, was because I realised I had reached a point where I had to move on, change. This exhibition has told me that there is no going back, whatever happens.

I have written more extensively about this here: “My resolution for this decade? I no longer want to be ‘John Ledger is an artist’” by John Ledger https://link.medium.com/EFKW0S4Sq3.