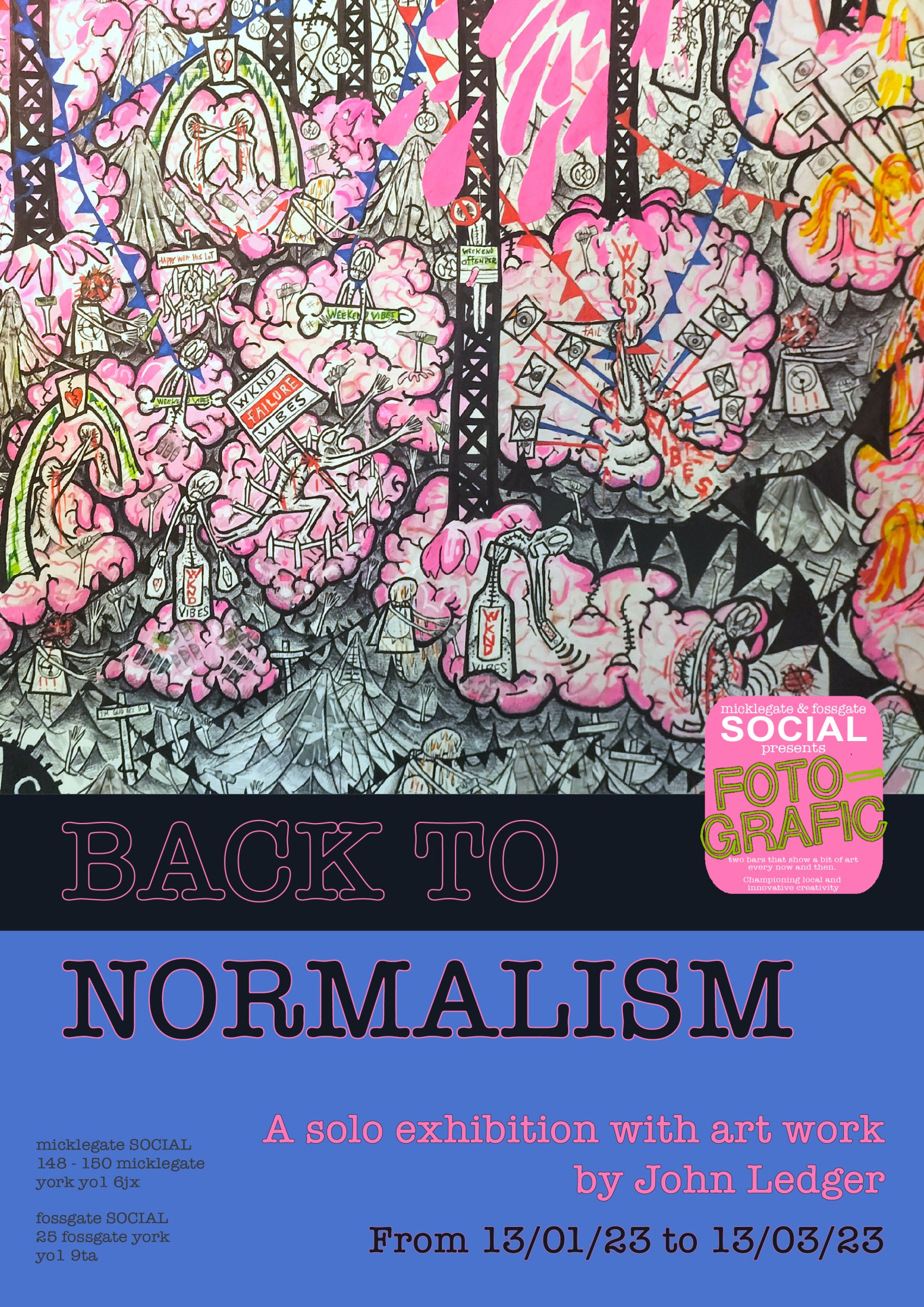

One half of ‘Back to Normalism’ is at the Fossgate Social, on Fossgate in York.

It consists of smaller scale works. However these works are of no less importance than my larger works.

One half of ‘Back to Normalism’ is at the Fossgate Social, on Fossgate in York.

It consists of smaller scale works. However these works are of no less importance than my larger works.

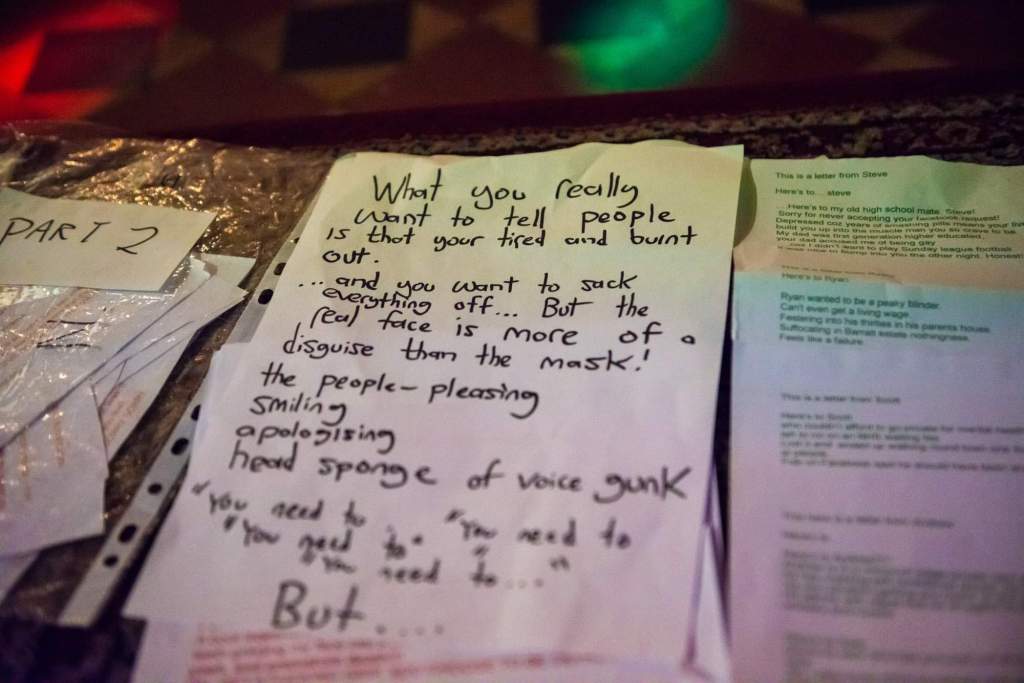

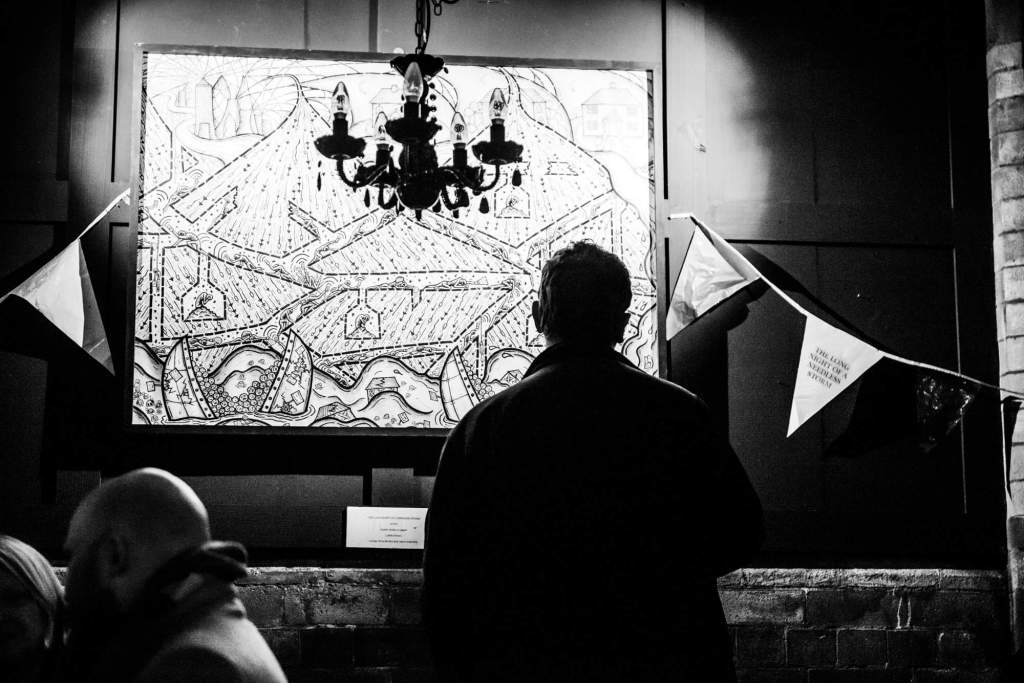

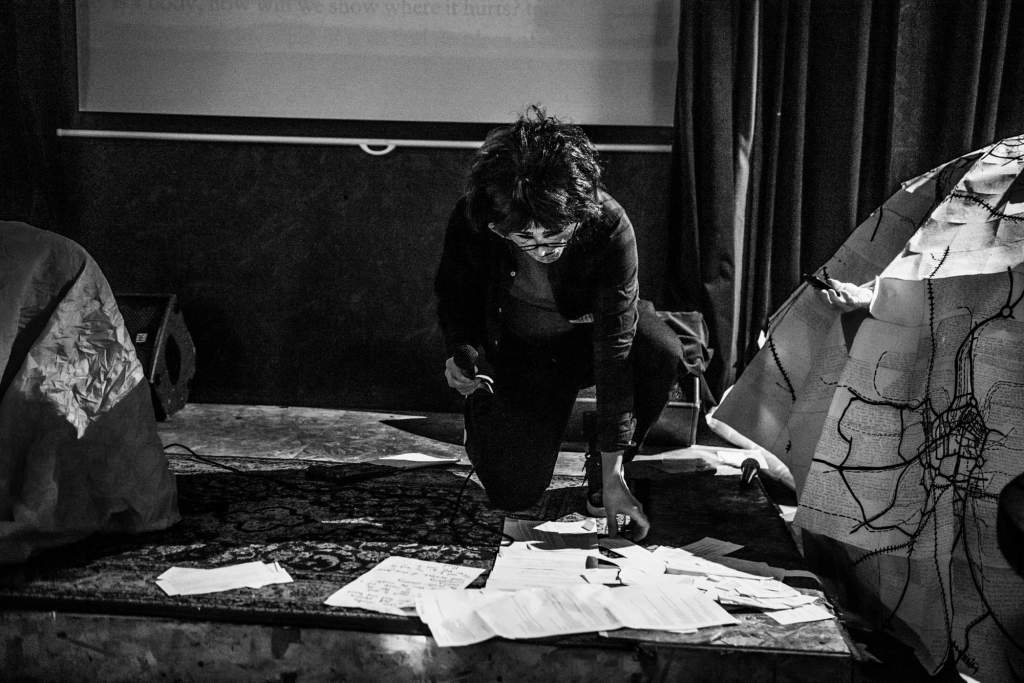

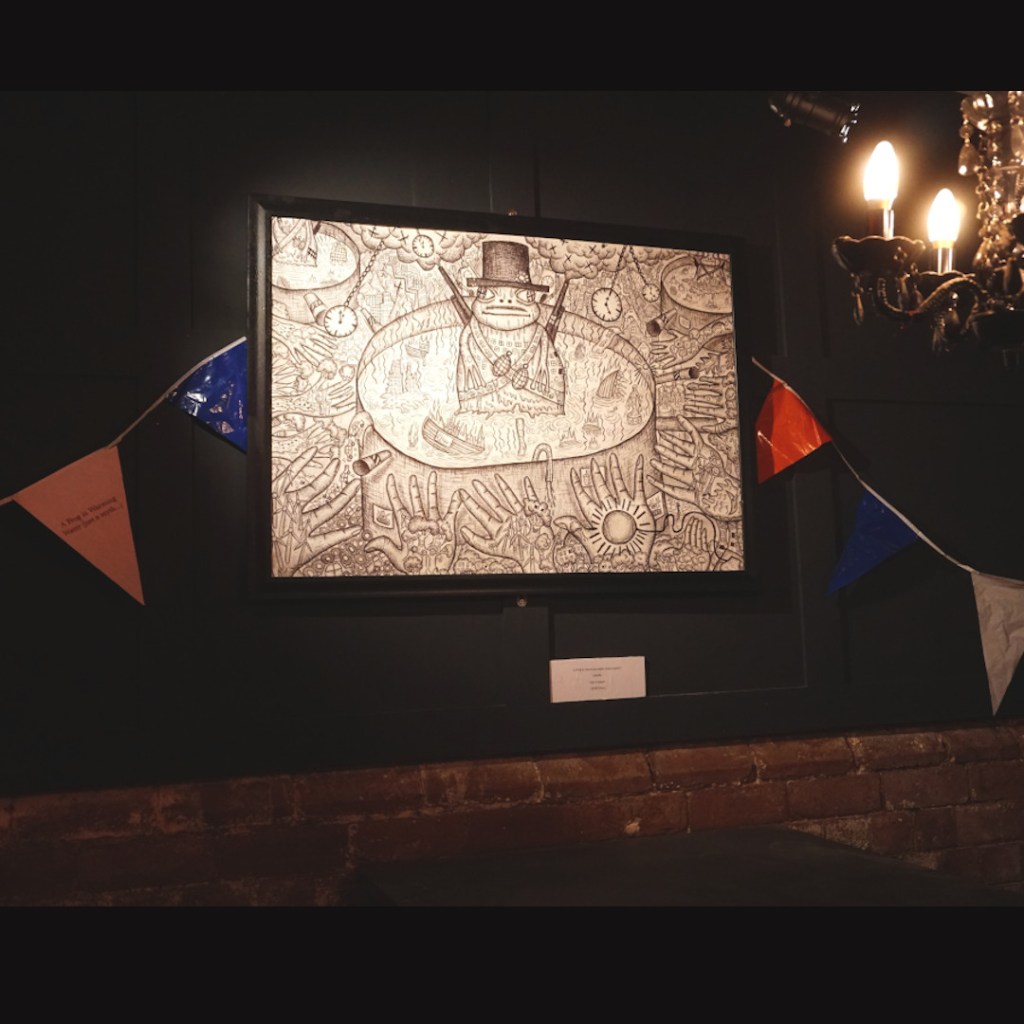

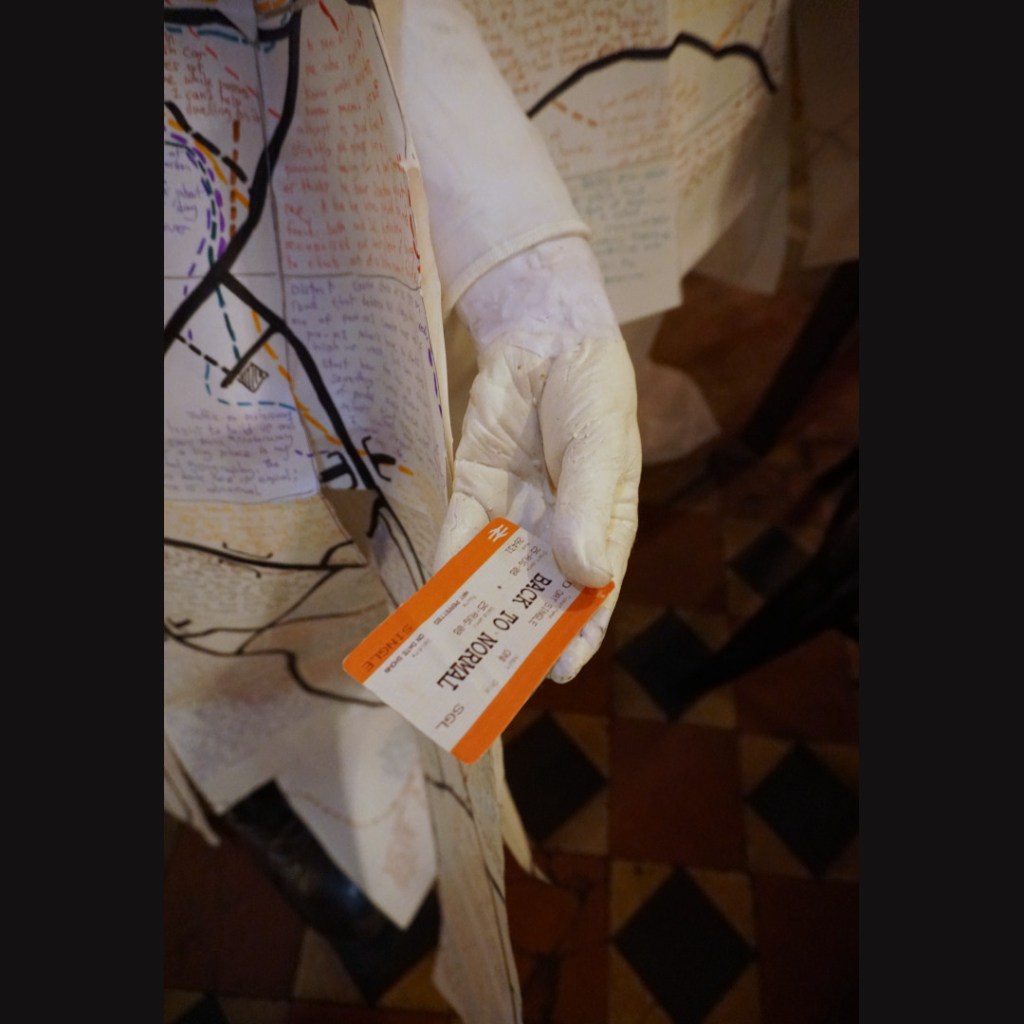

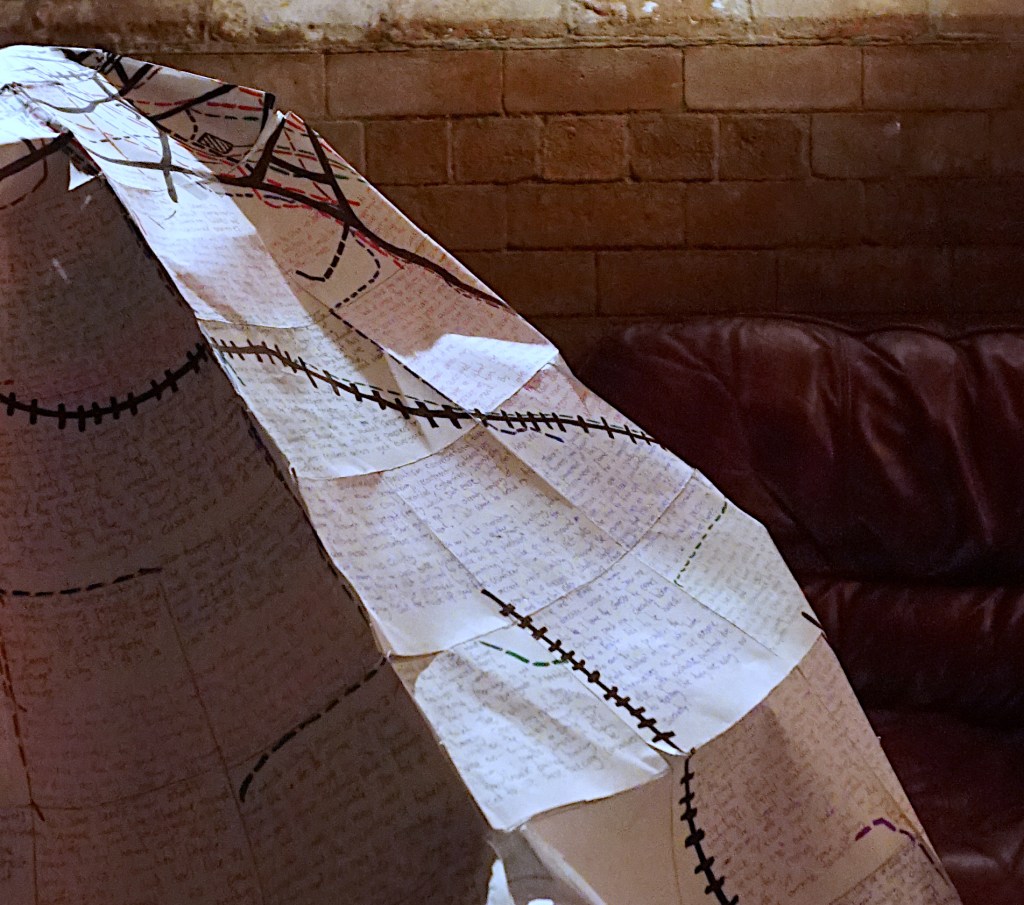

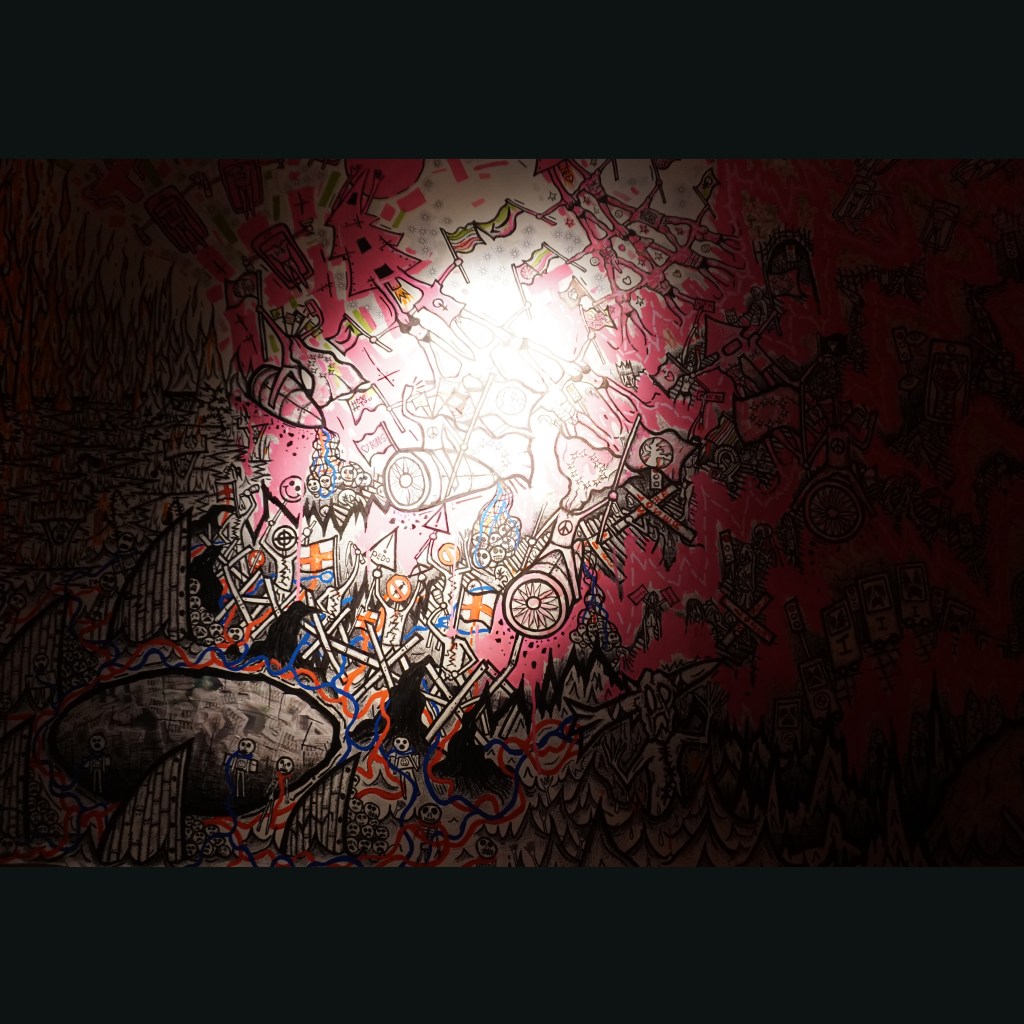

These are photographs from the preview of Back to Normalism, my most recent exhibition, which included a spoken word/sonic performance collaboration with myself and Adam Denton. Thanks to Mark Tighe for taking these pictures, which I feel perfectly capture the shows essence.

Also, I did this quite lengthy interview for Charles Hutchinson press prior to the exhibition, if you want to read it.

Thanks

I recently rediscovered photographs from late 2020 early 2021, a time that already feels foreign, even as still try to adopt to the ‘back to normal’ culture.

I had a studio in my home town at the time, and the area, already a semi-forgotten part of town, felt like the edge of the world during this period.

Some of these photographs are around there, others from the journeys to and from my studio and place of work.

Thank you to everybody who came to see the opening of Back To Normalism @micklegatesocial in York on Friday 13th.

Thanks to @stubbs_mike @wdus.art for making it happen.

The opening was centred around a collaborative performance with @zonal_markings which helped create something really special, which resonated with the ghostly sculptural forms which, like all ghosts, have since disappeared.

But the drawings remain, and only after a day of distance can I see how fitting they for this subterranean space beneath this historic city.

But the exhibition drawings are not only at @micklegatesocial but @fossgatesocial also. And are there to be seen until 13th March.

Time for some rest now…

I’m increasingly having feelings I had as a teenager, when I couldn’t do the things that helped me cope on a daily basis. When my legs were bad, because I’d run too much during that year, or the weather was just way too bad to go out, but I’d also eaten a full meal, and felt that feeling in my belly like a solid weight of judgement. I had to sit there and wait in pain for when it was ok to sleep (I didn’t have alcohol back then).

Why am I writing this now? Because I’m 39 in a week, and I know I can’t live like this anymore – on the run.

It’s got me nowhere. I’ve done some great things, but these artistic feats have by and large been an expression of how I feel about life, and not actually living that life.

But I also know that I’ve spent a long time being incredibly creative in designing routines and projects for myself that, in the short term, abate the horrible feelings about myself and life that are still there, waiting, from being a young person.

I always get scared these days when I write so honesltly. I fear that it will make ten people unfollow me on instagram (I will, in their eyes, become a ‘loser’), it will make people in my workplace think of me with suspicion, that I’m always on the verge of needing time off. But, more so, there’s always that sneering inner voice which isn’t necessarily warning me against exposing how “much of a mess(!!!!!)” I am, but says “I’m sure other people are suffering too, so why do your words need expressing – just get on with it?”

If I’d had been able to “get on with it”, I wouldn’t be writing this now.

My 30s have been a time when my inner battles have evolved from a daily protection from a self disgust in face of the threats I may face, to a self-disgust at my failure to do even the most basic of adult things. Part of this battle has been an inner fight to prove that my pain is real. This has undoubtably been a harsh 15 years for many of us, and I constantly fight the inner suggestion that I ” need to be quiet because there’s people far worse off than me”.

It’s true, I know full well: I live in a town with a hell of a lot of poverty, and a hell of a lot of homelessness since the Tories got in 12 years ago. It hurts me dearly everytime I see it, no more so, because I feel so much shame and guilt at the same time.

Shame and guilt are not mature feelings to have. I would love to feel more empathy and even possibly solidarity with these people. But I can’t do this until I face these horrible feelings about myself that I’ve had since being a young person.

It’s hard, because I have no choice now but to look at the feelings, and look at myself, in a way I didn’t dare do for 25 years. I have to face things that I’ve both run away from, and being ever more desperately trying to run towards (like finding a partner, and all that shit), and realise that at near-enough 40, I’m in a place I always prayed I’d never be in.

I’m here, aged 39, because I couldn’t face the horribleness I felt in the Now for 25 years – in the house, in front of the TV, on the late train home, on a pavement walking home – that sense of disgust and inability to deal with that in that present moment. I’ve got to face that now.

I’ve run faster, faster, faster over the past ten years, because when I stop, the voice I hear tells me that I have failed. I have to listen to that now, kindly.

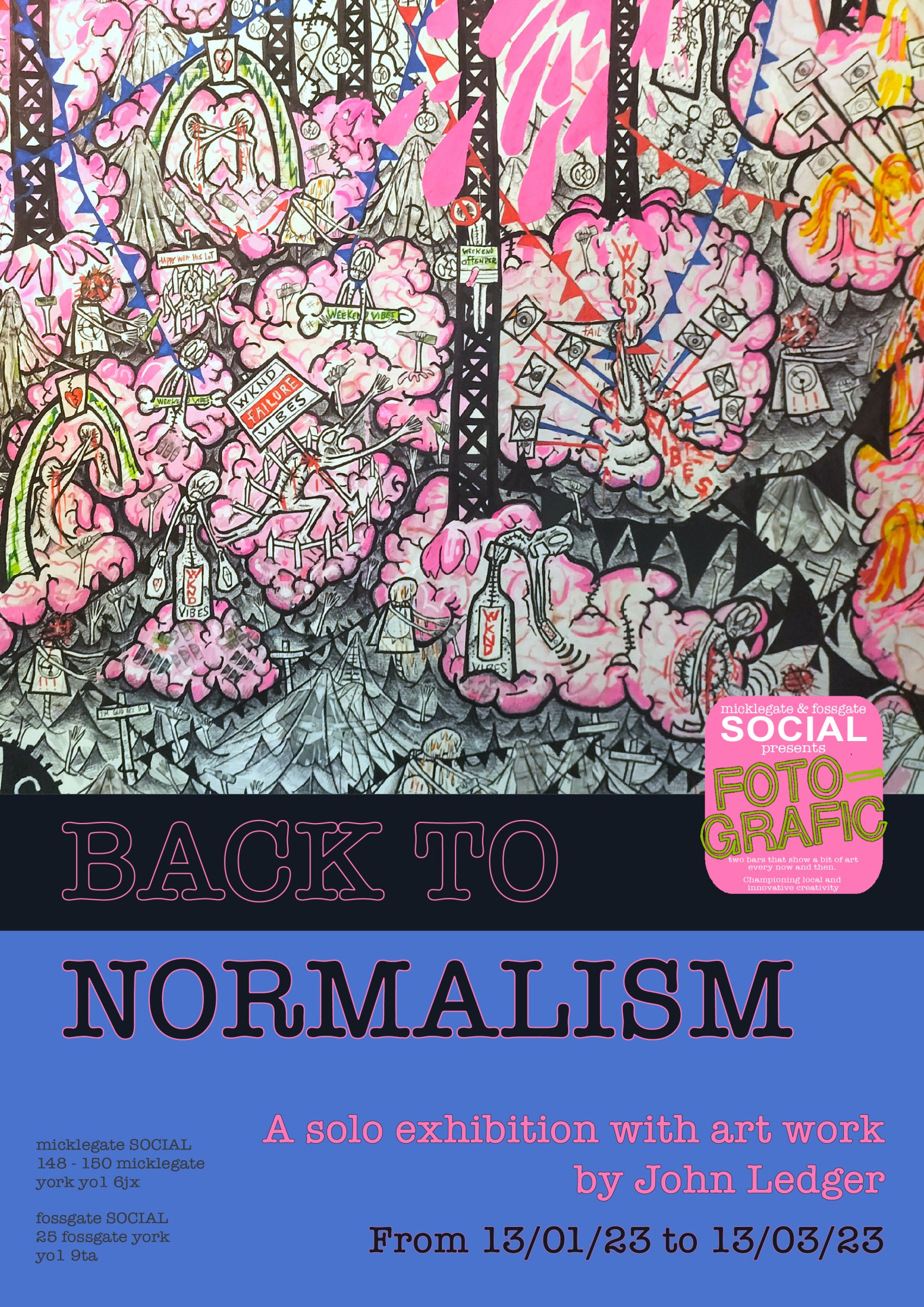

Apologies for posting this so soon after xmas, but this show is also very soon.

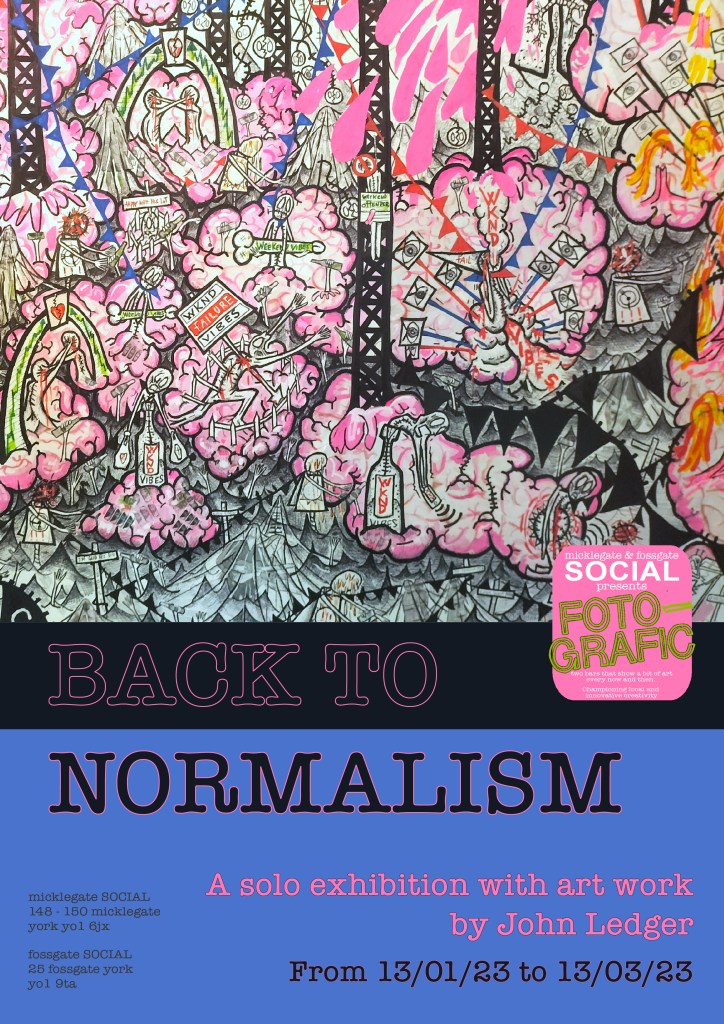

This time, however, there’s much more time to see the work: Back to Normalism will be held at both Micklegate Social and Fossgate Social in York from Friday 13th of January to 13th of March 2023.

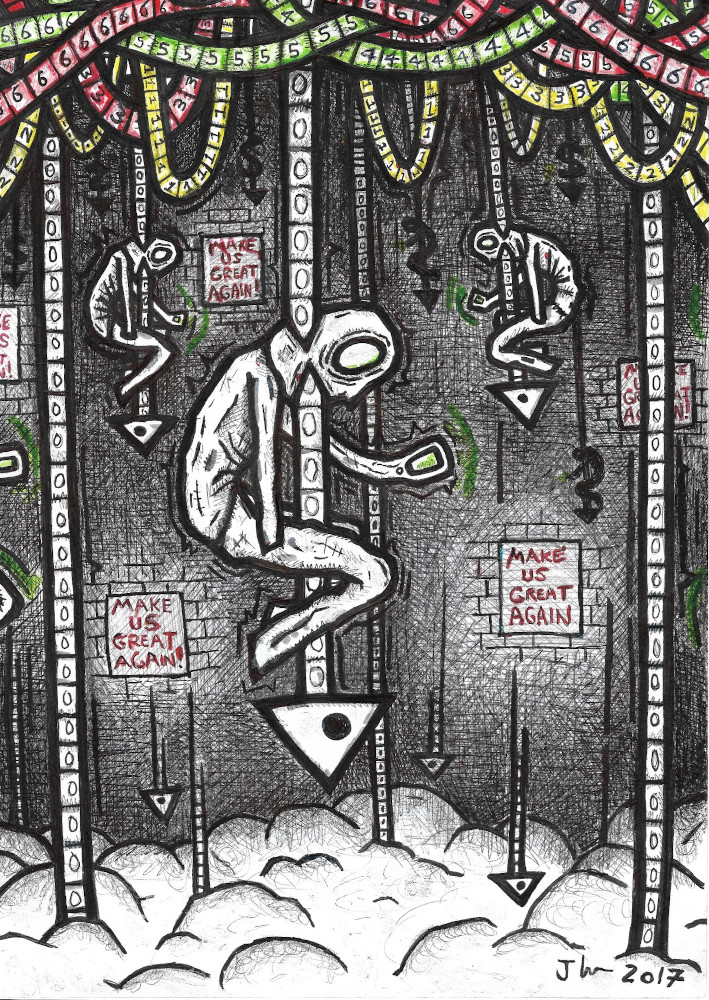

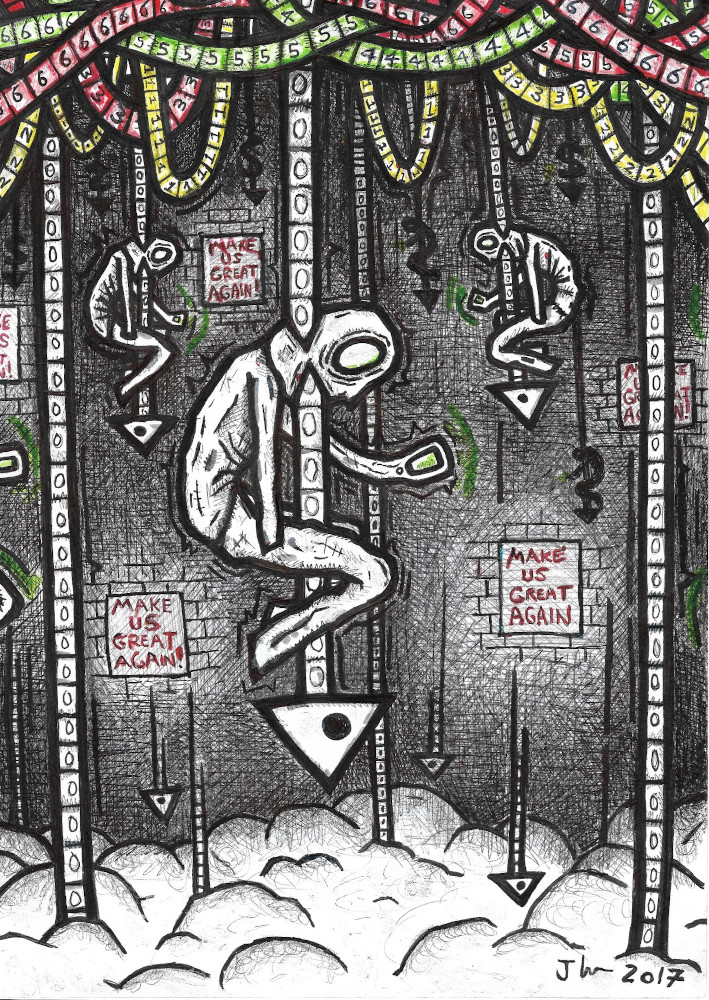

“Back to Normalism”, a solo exhibition by John Ledger (b. 1984, Barnsley, South Yorkshire), is about a time and culture that has been uprooted and disjointed by a series of crises, plus the reality distorting consequences of trying to repeatedly return to a `before´ moment. The exhibition uses a collection of the artist´s works that span form the present to the last 14 years, back to the 2008 financial crisis, in order to explore what John suggests with a culture that feels increasingly stuck and detached from itself.

Apologies for sharing this now. I know it’s not really in tune with the spirit. But I find that my work tends to dictate the timeframe of its own making, and I’m really super proud of this work.

Horrorsterity 2.0 will go into my upcoming solo exhibition ‘Back to Normalism’ at Micklegate Social and Fossgate social in York, starting on Friday the 13th of January. I understand exhibitions aren’t what’s on everyone’s mind at this time of year, but it’s not far away and I’ll be plugging it very soon!

All the best everyone.

First of all I’d to start by concluding that most people have found the last few years some of their hardest with little let up. I think I may have said before, COVID 19 has merely been a catalyst for the spiralling and emergence of so many things that we just cannot easily identify as singular issues. I’ve felt more out of breath. I’m pretty sure it’s not post COVID, but more the anxiety from feeling overwhelmed so frequently.

My year in projects has been largely defined by working on two very long term goals, with a goal of successfully triangulating the challenge of helping set up a grass roots art space in my home town, being able to actually exist as an artist in my home town, whilst also trying to build a good life for myself, a mentally and physically healthy life, with numerous tenets I’ve used to define what this entails.

These are the first years of my adult life where I have noticed some physical health issues, which I think is largely from living so long in a state of anxiety, and the behaviours that spring from that state. So the long term goal also has some urgency for me.

I can’t disclose too much, because these projects hang on threads. Successful Funding bids, random opportunities cropping up (the lifting of the clouds of corruption and endless austerity currently covering this country). The coming year could go one of two very different ways.

I began my making year with the simple enough act of getting back into drawing work in my first and only (so far as I know) period of COVID infection.

The series was labelled ‘Burn out’, but the 3 work here are individually labelled ‘It’s Easier to Imagine being a Billionaire on another planet…’ (itself a twist on the famous saying about capitalism, which I felt summed up our current variations of this situation), ‘ Enmeshed in the World’ and ‘An image for a Sheffield-based poet’, which was designed as a cover for a poet and friend, Jonathan Butcher.

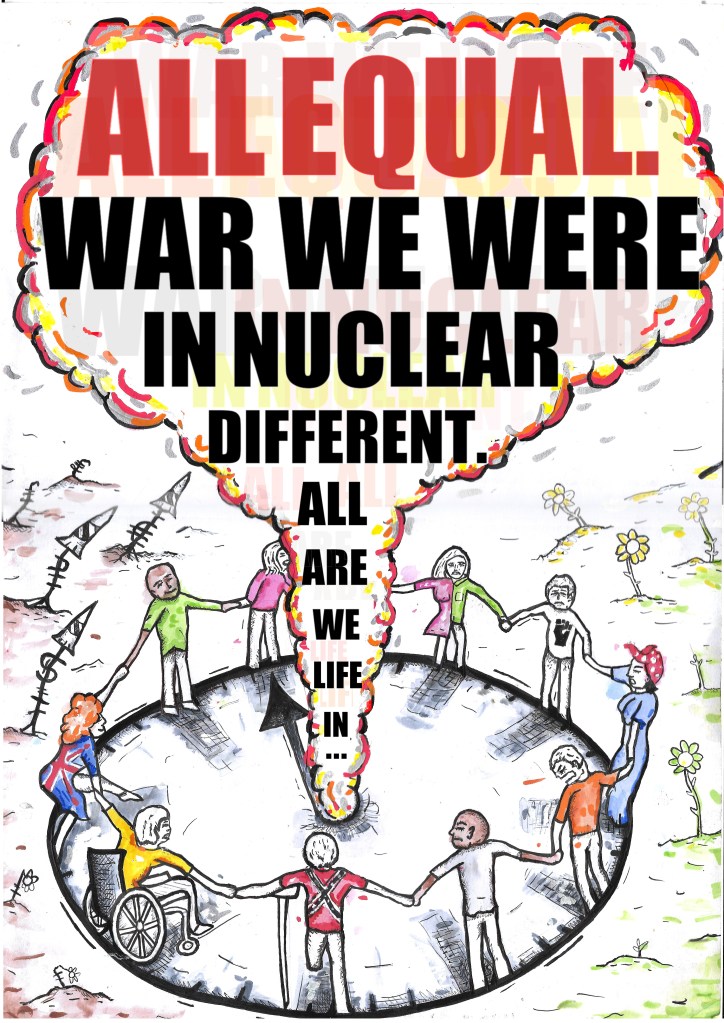

Obviously the carnage in Ukraine is one of the most unexpected horrors to have entered into reality this year. With the threat of nuclear war, that utter insanity, being highest since the end of the Cold War, I conjured my younger artist self, with his more heartfelt naivety to do something that my more weary and wary, more self-conscious older artist self would just find stupid: I made something close to a peace poster. (I still have some of these A3 posters to buy, with profits given to campaigns for the disarmament of nuclear warheads).

This informed the larger and much more invested-in work ‘All Those Promises…’ which was a more experienced response to the gap between promises and how reality turns out, on a governmental level right down to individual actions, disappointments that easily turn us towards cynicism.

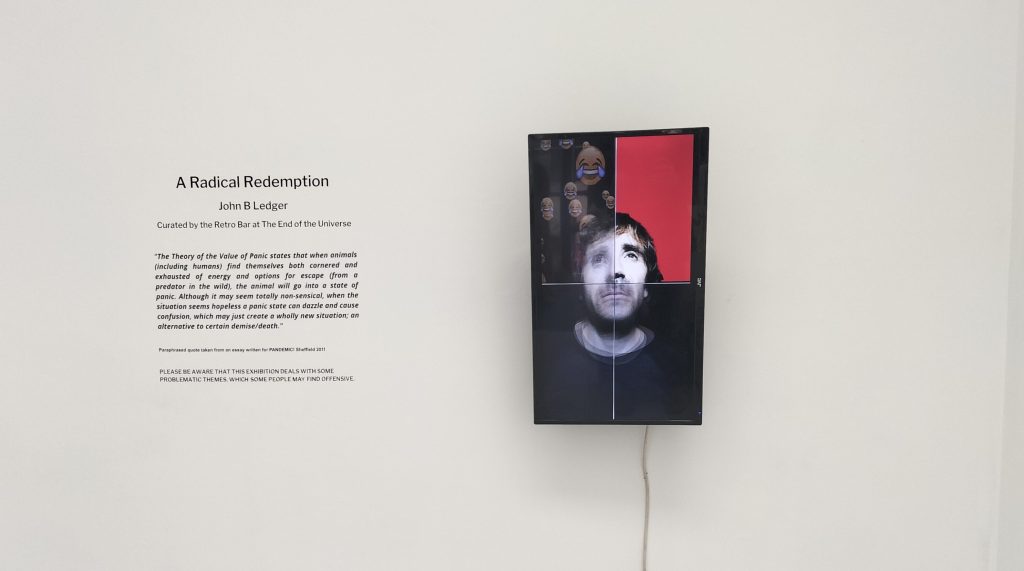

This became a final drawing to be included my first solo show since the pandemic. A Radical Redemption was held at Bloc Projects in Sheffield in May. It was an exhibition that was trying to make particles collide in the hope of creating a new situation out of thin air. The only thing was that these particles were abstract.

Although the exhibition did purposely try to generate a sense of claustrophobia as I invited people into a largely introspective space where, of course the world seeped in from all sides, but the interior was a semi-fictionalised account of what is hard to discuss beyond the ‘lived in’ – issues like toxic masculinity, mental health, addiction, and the prospects of radicalisation and madness from the perspective of me; being many things, but also white, straight male.

It was formed within the last two years, where a lot of us fell into our own heads, second guessing our every thoughts. The ideas for the show did produce a lot of concern from friends who were worried that I was putting my name in danger if someone took the information on show literally, but I felt it necessary, as I kind of cleansing of my most paranoid self- suspicions and accusations, and I wanted to do this in public, in an arts space, because I think there’s a lot that has been implicitly put off limits for debate in the arts (and no, I’m not implying there’s a lack of hate speech).

A Radical Redemption did broach a broader question however: do we need to imagine the impossible, bring into being something that didn’t previously exist, in order to get out a cultural and political logic that often seems so hopeless?

Afterwards I spent quite some time developing a performance that I’d agreed to put on for two separate events. This was quite a leap because I’d made a lot of what I’d call ‘situational spoken’ word pieces during the lockdowns as video works. I wasn’t sure how the creation of a scene and words would work in a live space. The work was to some extent about the suffering of ageing, but specifically in, to use a well-used term, times that are ‘out of joint’.

The trauma of the ‘back to normal culture’ that followed the first lockdown and the inability for contemporary society to publicly acknowledge the strains of the flesh, the organic, especially as a millennial, who are still referred to as young, even though we are clearly not.

This lead on to actually decided that we were in a moment of ‘back to normalism’, but whether this began during the COVID crisis, or at some earlier crisis, such as the 2008 financial crash, was harder to define. Nonetheless, it became the focus of the most ambitious drawing project (or at least the physically largest) I’d undertaken in years. This drawing has been designed to, and will hang from hooks once exhibited.

Most recently, as in completed today, is ‘Horrorsterity 2.0’. I don’t think this works needs any explaining.

This isn’t all, I’ve got an exhibition at Micklegate Social and Fossgate Social in the historic Northern capital York, starting on Friday 13th January. It’s really a 2022 exhibition beginning my 2023. I will share more information on this very shortly. All the best.

I’ve a long list of posts, which may or may not exist anymore, from way back into my 20s, documenting how hard I’ve found this time of year.

Truth be told, as I reach my late 30s I I believe I am coming to understand myself better, or at least give myself more forgiveness for the gut assumptions and verdicts I deal myself in those lowest of ebbs. I can approach my 40s with at least the intellectual knowledge of things I can do to try to treat myself better.

I reckon a lot of us found the last two years a hard time in which to work through a lot of our painful emotional knots. I went into 2020 with a clear-ish sense of what I needed to do to make a better life for myself. Then the pandemic happened, and it wasn’t the entire cause, but certainly the catalyst for a qualitative change to the coordinates of reality: ‘back to normal’ looked normal, yet it wasn’t – the structure of feeling had permanently changed.

I found myself battling against a lot of the acidy inner criticisms and defensive bitterness that I thought I’d mastered. I felt like I’d fallen backwards to when I first hit 30, with no plans for my future, surrounded by bright young graduates. It was like I was on a running machine treadmill with the gradient increasingly getting steeper.

Long story short all the worst verdicts on myself happen around Xmas. “You’ve got no life”, “you’ve got no community, no intimacy, no family” are all underpinned by a heightened sense of ageing: I believe the New Year is a much more powerful signifier of ageing than a birthday.

During the last two Xmas breaks I’ve tried to burn the oil, to double down on my ‘projects’, desperate to generate some sense of worth to my presence. Last year I had a meltdown and had to cancel the project that I’d put in all the work for in the first place.

This year I have actually got two important things I need to finish for early to mid January. They are two things that, when I feel better and well, I recognise as valuable projects. But I’m scared I’m going to burn out again.

It’s those feelings in the early hours, or when you’re waiting for a bus, or when you’ve spent a little long walking alongside a noisy road; those horrible verdicts about yourself that intensify. These cause the over-compensating self-worth substitutes to work on fumes. They accelerate the responses that cause burn out.

As I say, I’ve learnt a lot in my mid to late 30s. About the early causations of what would become an inability to embrace, embody and live with my adult self. Shame, like I was ‘wrong’, (the way I smiled, moved, but especially the intense way I spoke and behaved) which helped build an army of inner critics in my head that wouldn’t let me accept my being. And that I’ve spent my adult life trying to go the hard way round because I could never see my shape in any identifiabily worthy adult shape.

When these feelings dig down my identity as an artist is no longer something I should treasure, but beconed something I put a curse on, trying to gain a sense of human-ness through finally getting to the top of that ‘artist’ hill, where I’m crowned as a valid exercise in human-ing. But, I burn out, and I’ve pushed the boulder up that hill so many times, only for it to roll down again.

This could be the start of a life that works a little better. But I’ve got a couple of weeks where I’ve got to face the brunt of self verdicts and emotions I really don’t like the taste of.

At 5am this morning I asked myself the rhetorical question: when was there a time when you scrolled social media and felt better for it afterwards?

I’m pretty sure it’s rhetorical as the answer is “never”. I think, if I manage to say that to myself enough over the next couple of weeks I may just about make it to mid January in a decent state.

When I worked as a front of house member of staff in a nearby art institution, we had a saying to describe certain visitors who would arrive from, let’s be fair, mainly London and South East: ‘Columbusing’.

The males doing the ‘Columbusing’ would arrive towards the end of the day, and step into the gallery, like they’d stepped off a boat into a land ‘untouched’ by civilisation. ‘Wow, how could such a place exist near Wakefield?’ as they walked past the staff like a European ‘discoverer’ would walk past the savages. (This particular gallery is situated between the ex coal mining towns of Barnsley and Wakefield and the former heavy woollen areas of Kirklees).

They weren’t doing this knowingly because it’s simply an expression of the very old relationship between ‘the metropolis’ and the rest of the land.

‘Columbusing’ came back into my mind as I read an article published today in the Guardian in which the journalist describes the sense of betrayal in areas that voted predominantly in favour of Brexit, 3 years after the Tories, under Johnson, won an election landslide on the promise of ‘getting Brexit done’.

I’m not intending to go into the larger concerns of the article, although the idea that a voter response to this god awful period of Tory Rule-by-Gaslight would be to turn to a party (Reform UK) that could soon be lead by Nigel Farage, is a worrying and a depressing reminder that the quagmire of a sense of ‘abandonment’ that was being articulated a decade ago, is still being dominated by fears and angers over immigration.

I’m intending to talk about how the relationship between the metropolis and the rest of the country is not only expressed via liberal media establishments like the Guardian, but kind of reaffirmed by theses articles. It’s a concern that when a place sees itself in the mirror of the mainstream media, which after all is a manifestation of symbolic power, its formal identity is constructed – it becomes what it is represented as being.

This is very much done in how that place is framed. Today’s Guardian article visited Goldthorpe, a small town on the eastern side of the Barnsley borough that has never really recovered from the aggressive closure of coal mines in the 80s and 90s. Barnsley is by and large classed as a deprived area, and everything in this article is true. But the Guardian and BBC only ever frame Barnsley through its poverty, and hostility to immigration. You can guarantee that if they don’t visit the town centre, they will visit one of the two G’s, Goldthorpe and Grimethorpe, both of which have become iconic places in their struggles ever-since the pits closed.

I like John Harris as a journalist, for example I like his UK road trip vlogs, I think he’s a journalist who genuinely seems to care about the people he interviews up and down the country. He recently visited places like Grimbsy and Grimethorpe, to discuss peoples’ post-Brexit struggles, the picture he painted was bleak and very true.

But, due to the ‘touristy’ nature that field work journalism assumes when it comes out of the ‘Metropolis’ and into the ‘savageries’, it is always in a position of waiting to be discovered and waiting to be ‘real’. I think John Harris is a good example, because he clearly recognises this, and acted on this in his vlog series ‘Anywhere but Westminster’, but it’s very hard to break down that colonial relationship that exists in the UK between Londonish institutions and the rest of the country.

8 years ago Channel 4 news visited Sheffield for the beginning of Nigel Farage’s UKIP campaign tour. I believe that the coverage framing was all but defined by the use of two words to describe Sheffield as a ‘northern town’. Sheffield is a city, perhaps also a conglomeration of other towns, which a total population of 800,000. It is not a town to anyone who lives around here. 2 years later Channel 4 news visited Barnsley the day after the UK woke up to find out that Farage’s UKIP aims of leaving the EU had been successful. The voxpops and the tweets by the journalist were framed by a sense of bafflement with these people who didn’t think and feel like they did. To quote Jarvis Cocker lyrics, C4 news seemed ‘amazed that they exist’.

Symbolic power in the UK continues to operate through the colonial relationship London has over the rest of the country. Even in times of grass roots media outlets on the internet, the big media establishments still possess the ultimate power to make a reality officially ‘real’. This doesn’t mean this relationship doesn’t operate internally, within London. For example, Grenfel tower fire in the borough of Kensington and Chelsea; it was only through their deaths that their situation became a ‘reality’. But when it comes ‘north’, sometimes the ‘truth’ it uncovers causes as much damage as the good intentions of the journalists. Nobody is individually to blame for Columbusing, but it reaffirms the colonial relationship much of the country has with London.