To speak with admiration of Blur still stokes fear of criticism, even to this day. I’ve read enough critiques of their class tourism in the 90s; the ease with which they simultaneously pantomimed the working class whilst being socialites in the Camden scene to make me feel like the only culture I’m allowed to talk about visibly has to have coal dust in its veins.

In 2024 we still exist through the colonial gaze of ‘the metropolis’, and well-meaning left-leaning intellectuals still often view the North and its people as exotic. But let’s not forget that the colonial gaze is easily absorbed by the object of the gaze, and I see enough evidence up and down that the object in question has begun to identify itself as it is exotically viewed by the metropolitan gaze.

This object is based on an image of the North that I believe is now also mere pantomime. Growing up in the 1990s , the ‘authentic’ footage of groups of burly young men (not through any fitness program enhancement) at Miners’ pickets in the 1980s looked as distant and exotic as it ever could have been. And that’s where I wanted it to stay.

I didn’t want to become my working class past. The past looked painful, conflictual, full of drudgery, hard faces and unhappy endings.

But to be honest, it didn’t matter anyway, as I didn’t look for what I didn’t want to see. I, in a bespoke playing out of Millennial expectation, became convinced that pain, the pain of working people, of intergenerational drudgery, of conflict, of all conflict, was coming to an end.

This was the 90s, and all I recall was this dominant sense of a dying world being superseded by a new one. And, at the time, it looked like a good thing!

And I genuinely looked up to bands who dressed like soft-faced middle class students, and soft-faced middle class students who dressed like bands, because I genuinely thought we would all be soft-faced middle class from now.

The future would softer, and kinder…

The grass wouldn’t be worn down by angry Sunday League football lads calling you a cunt when you couldn’t kick a ball as hard as ice, it wouldn’t be smeared with one dog shit per square metre, with the occasional syringe left on the top field. In fact, the grass would give way to a beach, and we’d be like Leonardo De Caprio, finding our beach – with All Saints’ Pure Shores playing in the background (although we know how that ended up).

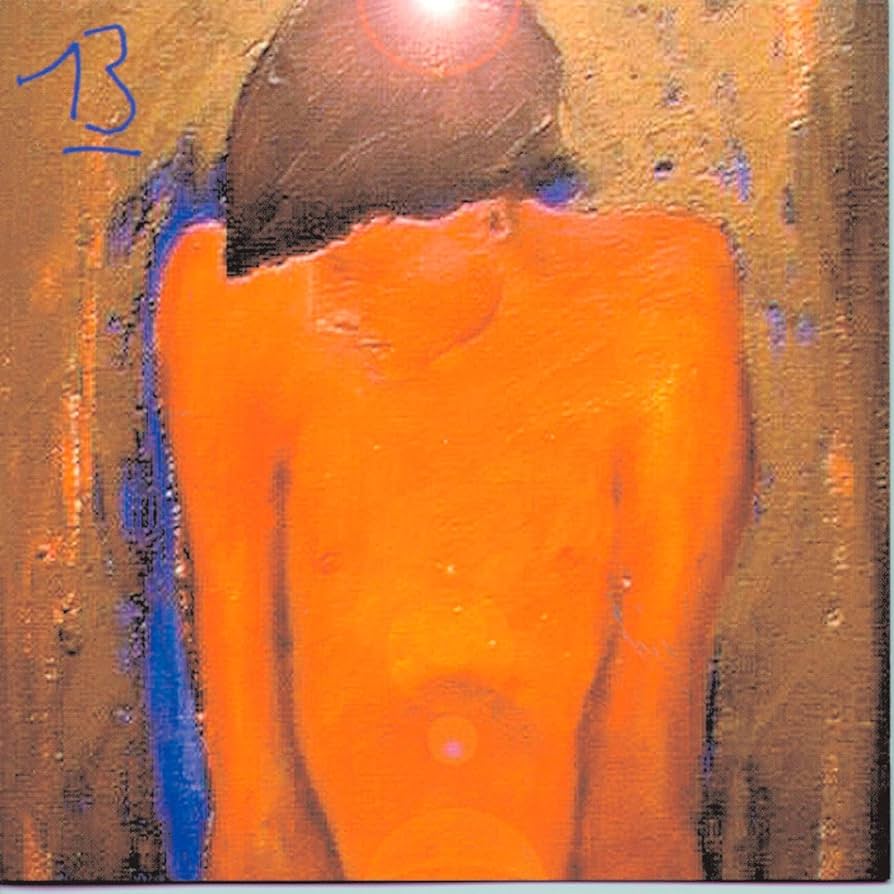

Why am I going into this? Well, when I heard Blur’s 13 25 years ago in the spring of 1999, this sense of a pain-free future on which I depended was unsettled.

I actually encountered it a month after encountering Radiohead’s Ok Computer, and in a way, they were a similar artistic statement, one I’ll try to return to.

In 1999 those months felt like epochs. I’d had my first major encounter with eating disorders and depression (although I didn’t know it at the time) and suddenly life felt long and tiring. I had felt that first mild gust of the void staring back at me.

Both 13 and Ok Computer gave me a taste of suffering without recourse to lullabies, without recourse to warm assurances. And I didn’t want to stay in their company for too long.

Luckily as Xmas 1999 arrived one of my cousins bought me the 10th anniversary edition of the Stone Roses debut album. ‘This is one she’s waiting for’ and ‘I am the Resurrection’: the album’s ending seemed designed to reassure emotionally repressed lads that all this strife would give way to a happy ending. I clung to this album like it was my millennial saviour.

25 years later, 25 years of living with some form of eating disorder and mental illness, I have inevitably kept returning to this 13, for understandable reasons.

In the process I have come to see it as Blur’s greatest record. It may not have been the groundbreaker of OK Computer, but in a way it chartered the territory that Radiohead couldn’t in the gap between their infamous Ok Computer (1997) and Kid A (2000) albums. 13 potentially took that object and went even deeper and darker than either of those records.

13 is conventionally known as Damon Albarn’s ‘breakup’ album – the creative aftermath of his celebrity relationship with Elastica front-woman Justina Frischman. But the idle reductionism of art must be one of liberal journalism’s worst crimes. Most artists find it frustrating to explain their works through a singular meaning. Art is a meeting point of many meanings that would not fit together if it wasn’t for the artwork – the more nodes that remain in the shadows, the better.

The record’s opener Tender, being a massive hit in an age of radio and TV, was absorbed by everyone, even those hostile to ‘indie’. And it brings back awkward but endearing memories of teenage drinking, the kind of drinking nobody really wanted to do but felt obliged to, and one of the ‘lad’s lads’ from up the road causing disturbances by yelling “come on, come on, love’s the greatest thing!” at the top of his voice.

It can’t have been just me who was unsettled to find out that the rest of the album takes a huge diversion away from such emotionally-supportive melodies.

There’s even a mute horror underlying the seemingly pedestrian second single Coffee and TV. In fact the pedestrian is purposeful; it reflects the suburbs, where life goes to quietly die, using anti-depressants as a levee against the pain of a meaningless life in a glorified waiting room for death. Perhaps it was Blur’s response to Ok Computer’s No Surprises?

Having grown older I now hear the sentiment of endurance in Tender. A determination to keep going, despite all, despite that which is around the corner. And with this, it underlies the reason I keep returning to the album. 13 set in motion a life lesson that I struggle to learn, even to this day.

Once in deep into the bleak of the album, I believe that the most important quality of 13 is the ‘in-between melodies’ which are almost between every primary song. Precisely because these small instrumentals are trapped between the primary songs, they become ghosts, in that they are stuck in one place, condemned to perform the same actions forever – in this case they forever haunt the recesses of the listener’s self-doubting mind. They threaten to trap you in the mental state you were in when you first encountered them.

These melodies remain undead; they can never be exercised, and surely it’s no coincidence that many of these instrumentals sound like they could be in the ballroom in Kubrick’s ‘The Shining’? Perhaps Blur accidentally stumbled into the ‘hauntological’ zone before the likes of The Caretaker did in the 2000s.

‘That’s just the way it is. Just the way it is. Just the way it is. That’s just the way it is.’

Hitting 40 has been difficult; the problems that developed roughly around the time I first encountered this album 25 years ago still dominate my life.

One thing that the better therapists have told me is that once you’ve had long term experiences with mental illness it will remain something you’ll be working out to the end of your life. Once you’ve encountered such a subjective state, you will never be quite the same. The struggle never ends.

What I have struggled to translate with my own experience is that this doesn’t equate to the situation being hopeless, far from it. And in this sense the challenge before me is to deal with my mental illness by accepting that suffering is intrinsic to all human life but that this shouldn’t be turned inwards as war against my ability to try to have quality of life.

The ‘quality of life’ part is the hardest part. And perhaps this is an existential crisis specific to a large proportion of Millennials who expected a better world than that of their parents, and found themselves encountering the slow dissolution of those certainties, alongside a persuasive sense that the future will be worse than the present.

I, in fear of returning to the textures of a life I was trying to escape from, potentially came to see myself as a tourist in my own habitat.

I thought it was my ‘duty’ to get out, to become that soft-faced middle class man, in his Berghaus jacket, in a leafy outer-city suburb, taking his children to art galleries on a weekend.

“I wasn’t really here, you see!”. I thought I was merely ‘passing through’, but unlike many people I’d encounter in typically more middle class working environments, I slowly came to realise what a real tourist looked like.

There were only so many times I could pick myself off the floor – one meltdown after another. The eating and thinking ghosts of 1999 kept returning, and found drinking, and after a while there was no more second chances. Not that kind of chance anyway – to be ‘like them’, the ‘them’ I felt I was expected to turn out like.

I’ve had to accept that I really am ‘nowt special, if that’, in a time where ‘capitalist realism’ has reasserted the believe that a life of drudgery and misery for the majority is an immovable certainty. And I admit I’m struggling to accept such a philosophy of life, even though it may be only option for the sake of better management of my mental health.

Which brings me to some complicated feelings about those ’90s bands who went to these difficult spaces and encouraged the listener to follow.

Blur were seen as class tourists in the mid 90s, when they collaborated with Phil Daniels to create a pantomime version of working class cockney life. But perhaps they, and Radiohead, remained tourists even when they explored depression, alienation and technology on the eve of the coming Millennium.

Like Jarvis Cocker’s Common People lyrics, which according to Owen Hatherley, he apparently once said were about Albarn as much as the infamous ‘Greek Student’ at St Martins, Blur and Radiohead could arguably always “stop it all, if it got too much“.

Perhaps 13 was Blur’s ‘lost week’, wandering around a landscape they could always eventually leave, to come back sorted and form a new band called Gorillaz (for example). Less fortunate artists, lacking the inner resources that are often formed in our upbringing, such as Cobain and Curtis, couldn’t “pass through the deserts and wastelands” and come back after.

This isn’t a criticism, if they were the tourists of a mental health pandemic that would be born out of the material and technological conditions of a world that just was about to arrive, they made masterpieces of it. And after all, weren’t we all invited to become tourists? With all the museums to working class life appearing in post-industrial areas in the 1990s didn’t we all assume we were all now tourists of a life that was no longer? As the Manic Street Preachers said, we’d all been told that this was the end.

That hard lesson is that it wasn’t. To make the most of what you do have, even as you repeatedly have to collect your own ageing bones off the floor, and put your increasingly diminished self back together again.

Perhaps after 25 years the song that hits me most, emotionally, is Trimm Trabb. Trimm Trabb comes towards the end of the album, rising quietly out of the swampy deadlands of Caramel to reach a crescendo of rage… and then silence. Again, this seems like 13‘s answer to another OK Computer song: Climbing up The Walls. Yet what brings me back to Trimm Trabb is a repeat of the weary-yet-comforting reassurance I had when I first heard it: that the storm is over now...

…Not suffering, not being human, but the traumatic experience. And this is the lesson that I am still trying to teach myself: life, as much as it may have once have been culturally ascertained, can never be pain free. Yet, however, illness and trauma can be overcome and it is important to fight to remember this.